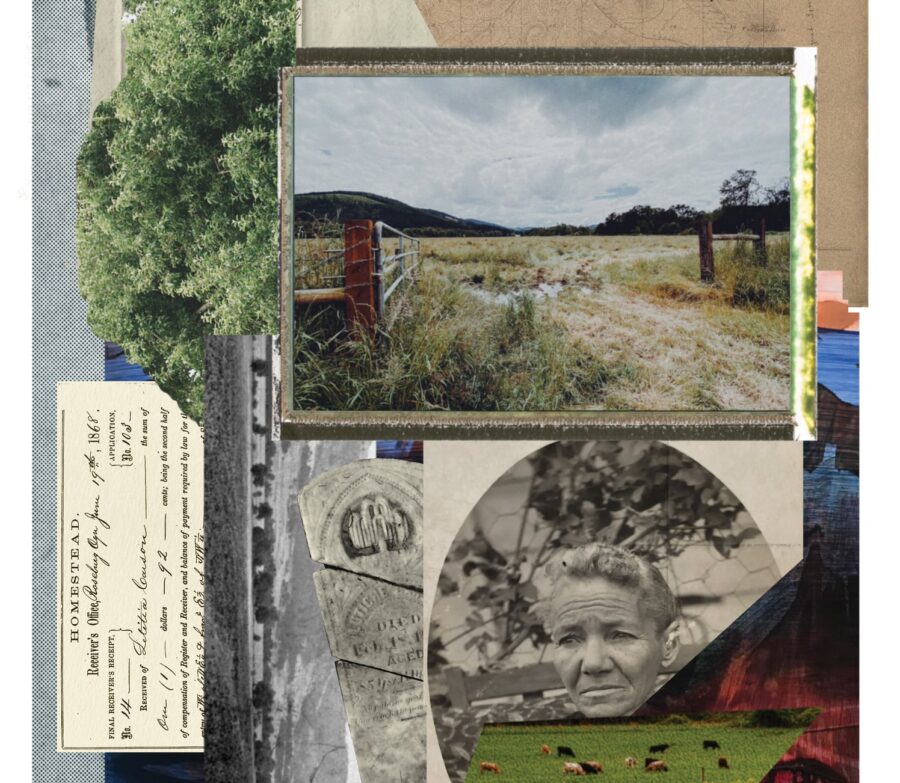

Eight miles north of Corvallis, Oregon, a wedge of open prairie known as Soap Creek Valley tucks up against the eastern foot of the Coast Range. A sweep of grassland rimmed in forested hills, the valley is both vast and sheltered at once. Here, in 1845, Letitia Carson concluded a more than 2,000-mile journey from Missouri. Though she’d survived the expedition’s many dangers—including the birth of a daughter along the way—her arrival in the fabled Willamette Valley would have offered little comfort: Letitia was a Black woman entering a region that had, among its first acts of governance, barred Black people from residing within its borders or claiming land.

Pioneer Letitia Carson Escaped Slavery to Became One of Oregon’s First Farmers

Racial justice advocates work to memorialize the historic homestead of Letitia and her white husband David Carson

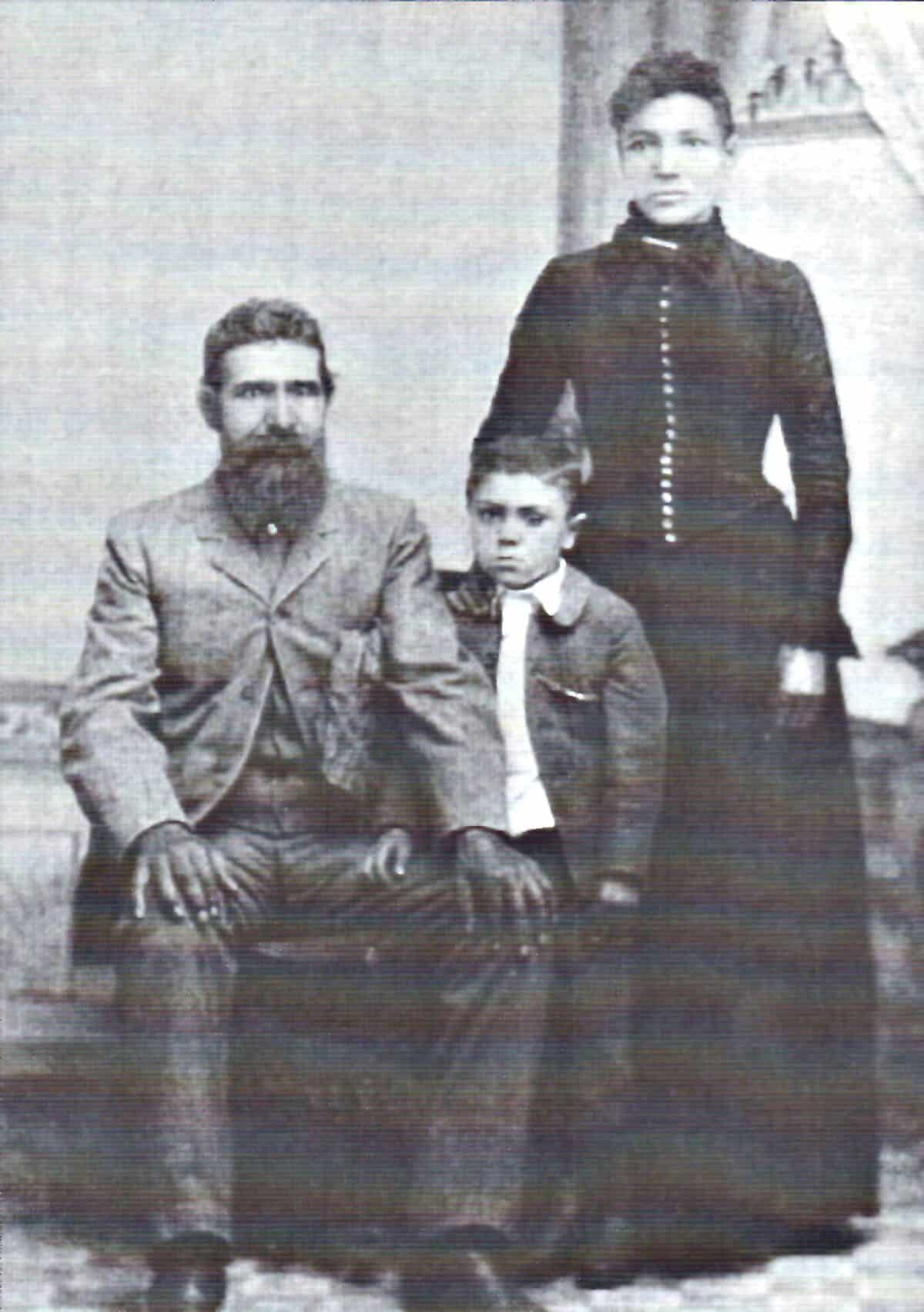

Born into slavery in Kentucky between 1814. and 1818, Letitia came to Oregon with an Irish immigrant named David Carson, their infant daughter Martha, who was born while on the Oregon trail near the North Fork of the Platte River in what is now Nebraska, and a cow she’d purchased en route. Letitia and David secured a land claim in the amount allotted to married couples: one section (one square mile) or 640 acres. On this land, Letitia grew potatoes, raised hogs, and tended to a growing herd of cattle. She became one of Oregon’s first farmers.

After five years of homesteading and the birth of another child, Adam, in 1850 the Carsons’ claim was halved to the single man’s allotment—one-half section or 320 acres—because county officials did not recognize Letitia as David’s wife. The Carsons cultivated their reduced acreage until 1852, when David died suddenly. Though he’d promised to make Letitia his sole heir, he left no will. A white neighbor named Greenberry Smith took control of David’s estate and swiftly dispossessed Letitia and her two children of everything they owned, denying them rights to their homestead and auctioning all their possessions—including Letitia’s herd of 29 cattle, the family’s Bible, butter churns and bedsheets.

Abruptly homeless, Letitia paid $104.87 to buy back a few of her belongings. With two cows and a calf, bedding and dishes, she and her children moved to Douglas County, a 160-mile trek south. By now, Oregon had passed the second of its three Black-exclusion laws. The first, enacted in 1844, decreed that any Black person who attempted to settle in Oregon would be publicly lashed 39 times every six months. The second was passed in 1849, and the third was written into the Oregon Constitution in 1857, where it remained until 1926.

Even in this decidedly anti-Black climate, Letitia refused to accept the injustice she’d been dealt. Instead, she sued Greenberry Smith—twice: Once for wages owed, and again for the theft of her cattle. Despite an all-white, all-male jury and judge, Letitia won both cases. Her victory, historians suggest, is testament to her tenacity, to the local respect she’d earned (enough to inspire a white man to testify on her behalf) and to the legal strategy she and her lawyer employed. At the time, debates over slavery dominated local and national politics. Most of Oregon’s settlers hailed from the Old Northwest and opposed slavery on economic, not moral, grounds. Believing that Black people, enslaved or free, would disadvantage white workers and non-slave-owning farmers, they wanted neither in Oregon. By identifying herself as David’s employee rather than his wife, Letitia aligned her case with the cause of free labor: A ruling that denied a Black woman payment for years of work would be akin to an endorsement of slavery.

This strategy won her compensation for her labor and cattle, but gave her no legal footing to reclaim her homestead. In 1857, it was sold to another white man. Perhaps it was the pain of this loss that forged in Letitia the resolve to acquire a piece of land that could not be so easily taken: one held free and clear in her own name. After the federal Homestead Act, which did not explicitly exclude Black people, passed in 1862, she applied for a land claim near Myrtle Creek and began cultivating a new homestead. She built a house, barn and granary, planted 100 fruit trees and raised cattle and hogs while serving as a local midwife. On June 19, 1868 (Juneteenth) after farming the land for five years in accordance with the act, Letitia received a certificate of ownership. She became the only confirmed Black woman in Oregon, and one of the first 71 people in the country, to secure a homestead claim. Letitia lived and farmed for the rest of her life on her own land.

After she died in 1888, her story slipped into obscurity. Letitia’s name shows up only once in the media of her time, a brief mention in the Oregon Statesman announcing her case against Greenberry Smith. Her unprecedented accomplishments were included in no newspapers or history books, and few details of her life were remembered even by her descendants. Meanwhile, her original Soap Creek Valley homestead passed from hand to hand, eventually becoming part of a World War II training camp that was later given to Oregon State University. All the while, the land gained value: today, those 320 acres are worth approximately $1,168,000.

Letitia’s story might have vanished altogether if, in the late 1980s, a graduate student named Bob Zybach hadn’t stumbled on an unusual detail while researching Soap Creek’s history. One land claim, he noticed, named “estate of David Carson” as the claimant. “That struck me as odd,” Zybach tells me. “How can a dead person claim land?” His question led him to the Benton County Courthouse, where a clerk dug out a file never before checked out. Inside, a stack of 180 documents detailed the Carsons’ estate sale and Letitia’s lawsuits. “It was like striking gold,” Zybach says. “Every item she’d owned was listed, all the legal records were there, and no one had touched them since 1856.” For the next three decades, Zybach and his research partner, Jan Meranda, transcribed century-old cursive, tracked down relatives, and located gravesites to piece together Letitia Carson’s story. Their findings revealed “one of the most interesting and consequential figures of 19th century Oregon,” says Zachary Stocks, executive director of Oregon Black Pioneers, the state’s only historical society dedicated to the African American experience. “Her story can go toe-to-toe with anyone we associate with early Oregon history.”

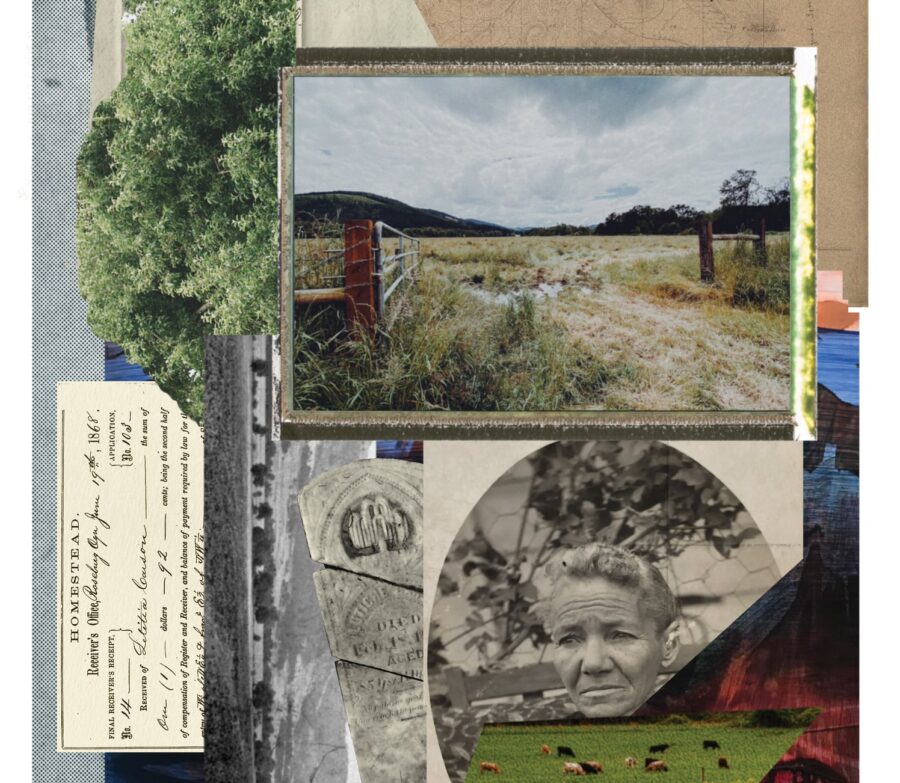

Now, a new Black-led collaborative called the Letitia Carson Legacy Project seeks to commemorate Letitia’s life and illuminate seldom-told aspects of Oregon’s history. At its heart lies Letitia’s original homestead site in Soap Creek Valley. Here, leaders hope to create a 21st century version of her homestead where the public can engage with Letitia’s story and future generations of Black farmers can access resources to support their success.

“What if we used this same piece of land that was taken away from Letitia and her children to create a site that promotes healing and environmental stewardship and history education?” Stocks says. “Maybe this could be a good model of what reparations could look like for us.”

IN FEBRUARY 2019, 174 YEARS after Letitia Carson arrived in Oregon, the first-ever Pacific Northwest conference of Black-identified farmers was held in Corvallis. The previous night, a pre-broadcast screening of a documentary called Oregon’s Black Pioneers was held at the same venue, and several conference attendees sat in the audience. The film explored the experiences of several of Oregon’s earliest Black residents, but it was Letitia who most caught the crowd’s attention.

“It was so powerful to hear her story,” says Shantae Johnson, a Black food-sovereignty advocate and co-founder of Mudbone Grown farm. Familiar with the state’s history of Black exclusion and whites-only land policies, Johnson was astonished to learn that a Black woman was farming in the Willamette Valley during that time and eventually came to own land in Oregon.

Johnson herself doesn’t own the land she farms; Mudbone Grown’s three sites are on leased properties. For farmers who haven’t inherited land or the capital to acquire it, she tells me, finding secure tenure is a huge barrier. And without it, farmers can’t make the investments necessary for long-term success.

Unlike many white farmers, Black farmers in Oregon haven’t benefited from the free land given to the state’s early white settlers through the Oregon Donation Land Act of 1850. The most generous land giveaway in U.S. history, this law validated claims made under Oregon’s provisional government which, beginning in 1843, enticed white settlers to journey west by offering white male citizens 320 acres each—640 if they were married. Claims of half the original acreage could be filed for another five years.

When the Oregon Donation Land Act expired in 1855, 2.5 million acres of land had been given to 7,000 white settlers. Arguably the most consequential of Oregon’s Black-exclusion policies, this law trails a stark legacy: Today, 96.7% of farm producers in the state are white, according to the 2017 Census of Agriculture. Only an estimated 0.1% of farm producers are Black, according to an analysis of the census data by Oregon State University. Johnson, who sits on the Oregon State Board of Agriculture, described attending an organization event, where she and her partner, Arthur Shavers, sat at a table with several other farmers. “Each farmer was saying, ‘I’m a fourth-, fifth-, sixth-generation farmer and I own 2,000 acres.’ But we couldn’t say we owned anything; nothing was passed down. If you don’t have land, you don’t really have anything to pass on to your family. That’s where equity and wealth is built.”

In the theater that February night, Letitia’s story struck a particularly resonant chord for Johnson. It not only illustrated the depth of Oregon’s anti-Black history, but also revealed the perseverance of a woman who dared to insist on justice and ultimately attain something still rare for Black farmers in the state: land ownership.

A few seats down from Johnson sat Lauren Gwin, associate director of Oregon State’s Center for Small Farms and Community Food Systems. Like Johnson, Gwin had never heard of Letitia Carson. On the way out of the theater, the two women started talking, and Gwin mentioned that Letitia’s original homestead site was now owned by OSU. At that, Johnson turned to Gwin. “How do we find out more about this story,” she asked, “and what is happening with that land?”

It turned out that the land was part of the College of Agricultural Sciences’ Soap Creek Beef Ranch, a cow-and-calf operation used for hands-on learning and research. The Carsons’ 320-acre land claim, located in the middle of the 1,200-acre ranch, remained open pasture. It was a rare find: a site where a significant piece of Oregon history took place that remained intact and owned by a public university. All this presented a powerful opportunity, Gwin believed, for OSU to use its resources as a land-grant university to address racial inequalities.

Gwin and Johnson began to discuss how the Carson land could be repurposed to serve restorative justice. “Early on, we thought: What if we could acquire that land and set up a land trust to hold it for Black farmers?” Gwin tells me. She reached out to Oregon Black Pioneers and the Linn Benton NAACP, while Johnson and a team of other Black women founded the Black Oregon Land Trust, a nonprofit that conserves agricultural land for Black farmers. Together, leaders from these three organizations and OSU established the Letitia Carson Legacy Project and outlined a collective vision for the Carson land. They imagined a living history center based around a re-creation of Letitia’s homestead; public tours and community events; agricultural research and training programs to support Black farmers; and opportunities for these farmers to once again cultivate this land. The site would become the first monument in the Pacific Northwest dedicated to interpreting the life of a rural Black woman.

Jason Dorsette, president of the Linn Benton NAACP, brought the Legacy Project’s ideas to OSU’s leadership. “The initial conversation was easy: the discovery phase, the story of this fantastic, phenomenal woman,” he tells me. “All that was good and great.” But when Dorsette and other project members raised the possibility of shifting the use of the land, momentum slowed. In late 2020, following that summer’s call for a national reckoning with racial injustice, the college signed off on the project’s design phase but made no promises in regards to the land.

TWO YEARS LATER, ON A DRIZZLY December afternoon in 2022, I met Larry Landis at the northern edge of the Soap Creek Ranch. Landis, a recently retired OSU archivist, has been working with the Legacy Project to help disseminate Letitia’s story and link it to contemporary Black farming in Oregon. He’s collaborated with sociology graduate students and faculty to conduct and archive oral histories of Oregon’s current Black farmers, ensuring that their stories, unlike Letitia’s, won’t be so easily erased from public memory. That afternoon, Landis took me to the Carsons’ homestead site to look at the land, an archive of its own.

We set out across a soggy pasture, passing a concrete WWII-era bunker tangled in blackberries before reaching the place where Letitia’s cabin is believed to have stood. I turned southwest to take in the view: Open grassland spread across a flat basin floor, then slimmed to a ribbon and disappeared into forested hills. No buildings or roads fell within sight. Half a mile away, a herd of elk lay veiled in a drift of fog. Catching our scent, the animals stood and ran.

At a glance, the place appears remarkably similar to how it might have looked when Letitia and David first arrived. But a keen eye would note differences: Canada thistle, an invasive weed that thrives in disturbed soil, proliferates. Pasture grasses displace native rushes and sedges. Camas, a flowering plant once abundant in open prairies like this one, persists only in sparse patches.

When the Carsons reached Soap Creek in 1845, they were among more than 16,000 overland settlers who came to Oregon between 1844 and 1850 in pursuit of those copious land giveaways, undeterred by the fact that the authorities promoting free acreage—first Oregon’s provisional government, and later the United States—had no legal claim to the land they offered. No treaties with the region’s tribes had been ratified; the land belonged to Indigenous people.

David and Letitia’s claim was located in the homelands of the Luckiamute Band of the Kalapuya, whose descendants are now members of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde and the Confederated Tribes of the Siletz Indians. Once a tribe of around 20,000 people, the Kalapuya stewarded the open prairie landscapes of the Willamette Valley for over 14,000 years, using fire to clear encroaching shrubs and trees, enrich soil, and encourage desirable vegetation. In the 1830s, the tribe lost 90% of its people to a malaria epidemic. “So when Letitia arrived in 1845, we’re talking about a people in recovery, people trying to regain their populations and culture,” David Lewis, a scholar of Kalapuya history and member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, tells me. But the influx of settlers like the Carsons, eager to claim Kalapuya land 320 acres at a time, precluded their recovery, denying them access to the resources upon which their survival depended and pushing many to starvation. Native foods were destroyed as settlers plowed carefully managed meadows and ran pigs and cattle across prairies. By 1851, the entire Willamette Valley had been claimed by settlers. Cut off from their means of survival, the Kalapuya had no choice but to sign the 1855 Willamette Valley Treaty, ceding over 1 million acres to the U.S. They were then forced onto a 61,000-acre reservation in the Coast Range.

On the Carson land that December afternoon, Landis pointed to a ruffle of black plastic protruding from the rain-drenched soil. It marked one of five test pits dug during an archaeological exploration organized by the Legacy Project. Here, a quarter-sized shard of mid-19th century transferware pottery was found. Along with this possible relic of the Carsons, the dig unearthed several artifacts left behind by Indigenous toolmakers: basalt flakes, chert cores and pieces of obsidian.

For the Legacy Project, and its central aim of telling a more truthful account of Oregon’s past, this layered history presents a challenge: How to commemorate a settler’s story without obscuring the devastating legacy of settler colonialism on the region’s Indigenous people? But many of the project’s leaders also see an opportunity here. “From the beginning, we’ve acknowledged that Letitia’s story was made possible only because of the violent removal of the Kalapuya,” Gwin tells me. The Soap Creek site provides the chance to tell a multi-vocal history of a single piece of land—one that includes perspectives from the Black and Indigenous communities connected to it—in order to reveal a more complete picture of the scope of the white supremacist ideologies embedded in Oregon’s history.

Figuring out how to achieve this ideal remains a big part of the Legacy Project’s work. “We’re going to be doing a lot of community-building and hearing from the Kalapuya to ask, ‘What is the vision around Black and Indigenous solidarity in regards to this land?’” Johnson says. “Because there’s a lot of richness there, so many stories.”

The Legacy Project has reached out to the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians to invite their collaboration. So far, neither tribe is officially involved, and I was unable to reach tribal officials for comment. In the meantime, the Legacy Project is consulting with Indigenous faculty at OSU and community leaders, including David Lewis, an assistant professor of anthropology and ethnic studies.

“It’s not enough anymore to just have a little plaque with our name on it,” Lewis, who formerly worked as the manager of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Cultural Resources Department, says. If tribes are going to invest in this project, he believes, it needs to offer tangible benefits and an equal voice in the process.

Lewis sees possibilities in the Legacy Project. Remnant populations of native plants, including camas, a traditional staple food of the Kalapuya, persist on the Carson land, indicating good potential for restoration. He’d like to see the Legacy Project work with tribal leaders to restore sections of the property to native landscapes and confer gathering rights to tribes. This would honor Kalapuya culture and history while creating opportunities for Indigenous studies students and faculty to engage with the land. But, Lewis says, “There’s a reluctance on the part of Ag. College to take the cattle off the land. That doesn’t bode well for a true restoration project.”

Jason Dorsette of the NAACP also expressed skepticism about the sincerity of OSU’s commitment to both communities. He’s wary the university will try to use the project for a “two-for-one,” checking off its obligations to both groups without allocating additional resources. Dorsette fears that Letitia’s story and the Black experience in Oregon will be pushed to the side or watered down in service of a multicultural vision—one in which people of color are lumped together and their communities’ unique experiences and histories are obscured. Lewis shares this concern. “Under this new BIPOC label, it’s like we’re all in the same boat,” he says. “We’re not.”

Both Lewis and Dorsette believe it’s possible to create an interpretive site that honors each community’s histories and connections to the Carson land—maybe even one in which the whole amounts to more than the sum of each part. But accomplishing this would require additional resources and land, which OSU hasn’t committed to. And that squeeze is creating tension between the two communities, Dorsette tells me. “I find this to be one of the oldest tricks in the book, to pit communities of color against each other so we’re fighting for presence, for attention,” he says. “I get a little emotional because it reeks of anti-Blackness and white supremacy ideologies that cause communities of color to compete for funds that a university like OSU should just make happen because it’s the right thing to do.”

AT THE EDGE OF A GRASSY SQUARE on the Oregon State campus in Corvallis, a stately brick building houses the College of Agricultural Sciences. I’d come here one winter afternoon to talk with Dean Staci Simonich. No sign marked the door, and I wasn’t sure I’d found the right building until I stepped back, craned my neck and saw a row of colossal capital letters towering above the fourth-story windows: AGRICULTURE.

In 1868, the year Letitia received title to her Douglas County land, OSU was designated Oregon’s land-grant university. Created in part to bolster the nation’s agricultural industry by institutionalizing farm research, land-grant universities were federally funded via land expropriated from Indigenous tribes. OSU received 91,629 acres from several tribal nations—including the Kalapuya—which were sold to raise the endowment principal of what would amount to $4,182,259 today. The university has since become the largest in Oregon.

In her office, Dean Simonich expressed enthusiasm for Letitia’s story and the Legacy Project. She tells me that the College of Agricultural Sciences has recently “upped its game” in regard to diversity, equity and inclusion, and she views the project as part of that work. “We want to show that this is not your grandfather’s College of Agricultural Sciences,” Simonich says.

I asked her if the beef ranch was willing to relinquish the Carson land to accommodate the project’s goals. “It’s not determined yet,” she tells me. “We’re still developing the vision for what the project could or might be.” And cattle ranching, Simonich says, is an important aspect of Letitia’s legacy. She points to a frame on her office wall, which held a cherry-red silk scarf printed with dozens of cattle-brand symbols surrounding the words Oregon Cattlewomen. “I got it at a silent auction,” she tells me. “It’s 70 or 80 years old. So you see there’s a strong heritage of cattlewomen in Oregon, and Letitia was among the very first.” Today, cattle ranching is crucial to Oregon’s agricultural industry. After greenhouse and nursery products, cattle and calves are the state’s most valuable commodity, followed by hay and dairy.

Simonich believes the beef ranch and the Legacy Project can co-exist. “I’m a ‘both/and’ person,” she says, “not an ‘either/or.’” Some goals can be achieved without altering the ranch’s current use of the land: Occasional events can be held, archaeological surveys conducted, a memorial marker erected. But the project’s fundamental aspirations—creating a historic homestead where the public can learn Letitia’s story, cultivating Native landscapes and First Foods, and restoring the land to Black and Indigenous stewardship—will require the beef ranch to give up at least part of its claim to those acres. “That section is some of the best grass we have,” Simonich says. “It would be hard to lose that.”

One of the first calves of the season had slipped out between the rungs of its corral on the frosty January morning I visited ranch manager Mike Hammerich at the Soap Creek Ranch. Once weaned, Hammerich says, this calf and the 120 others expected this spring will be sold for around $1,000 each. From where we stood watching the calf squirm back through the rails to its mother, Letitia’s cabin site was out of view. But we could see parts of her 320-acre claim: flat grassland giving way to sloping hills and eventually woods. That land, Hammerich explained, produces most of the hay the ranch depends on and provides essential pasture. “Losing those acres would be devastating,” he says.

Still, Hammerich supports the Legacy Project and believes a portion of the land—five or 10 acres—could be fenced off for an interpretive center without harming the ranch. In the meantime, he moves cows and works to accommodate the project’s events, like last summer’s Juneteenth celebration and a field trip from the recently renamed Letitia Carson Elementary School, where he was impressed to see fourth-graders learning Letitia’s story. “I grew up in Oregon and I never learned any of this history,” he says. “I learned about slavery, of course, but nothing about Oregon’s history of racism and Black exclusion.”

If, as the dean says, Oregon State is “not ‘your grandfather’s agriculture college,’” whose is it? According to OSU’s Office of Institutional Research, 72% of students in the College of Agricultural Sciences are white. Black-identified students make up 1.3%, and Indigenous students make up 0.8%. “If we look at our student success metrics, we know we are not doing as good a job as we need to around serving Black and Indigenous students,” says Scott Vignos, the university’s chief diversity officer.

In 2016, following a student protest about racism at OSU, the university established the Office of Institutional Diversity to address this persistent problem. “Part of that work involves building relationships that have been injured or never built in the first place,” he says. By connecting the land’s various stakeholders—Black-led community organizations, tribal partners, students and faculty—Vignos believes the project could present a unique means of doing that work. But it won’t be easy. “Anytime we talk about almost any site in the West, we are going to find at once really exciting, but also painful, stories, and pain that has not been reckoned with, so that’s going to be a big part of this process.”

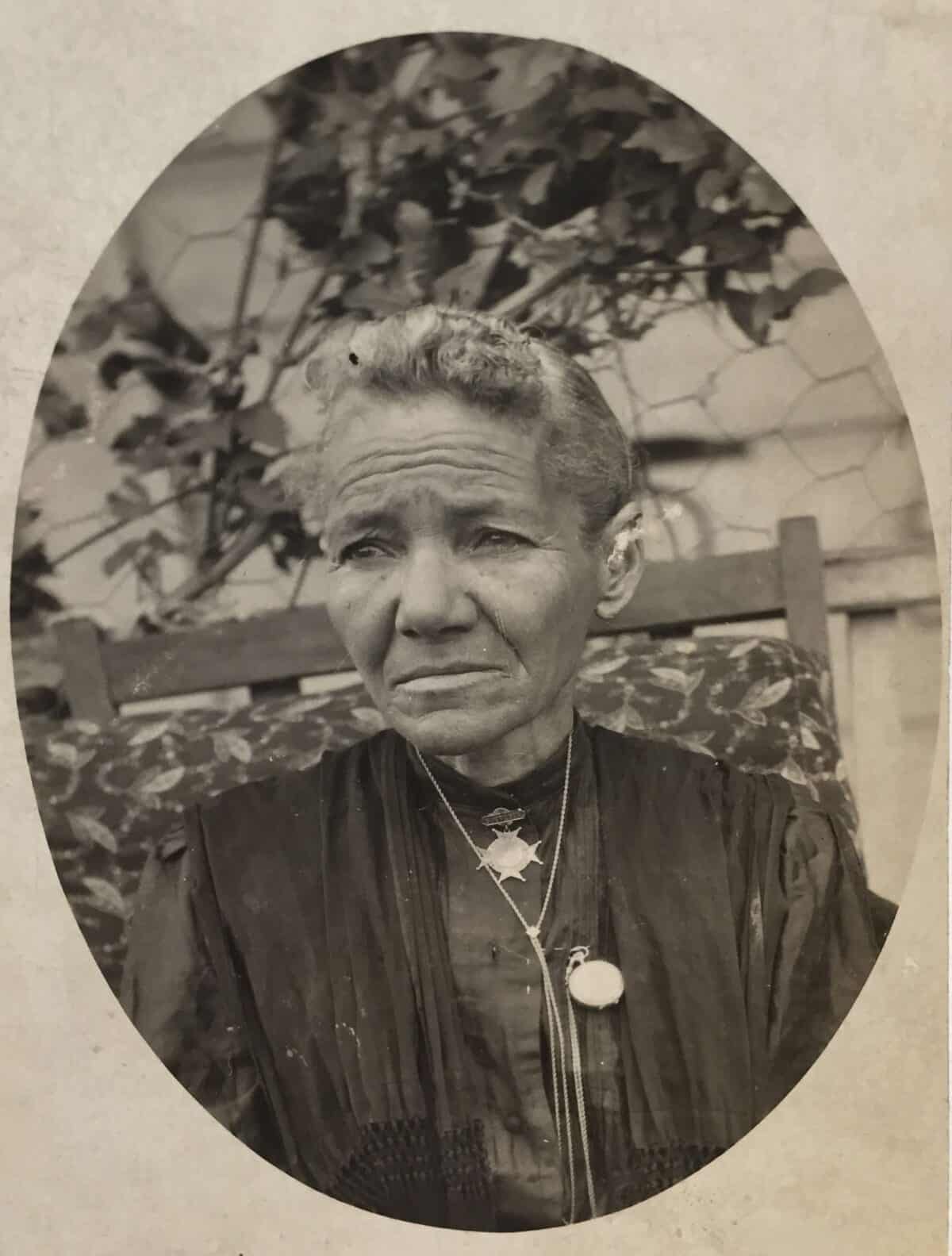

THREE MILES ACROSS TOWN, in the library of Letitia Carson Elementary School, a glass case holds two intricately woven forms: a traditional Walla Walla woman’s hat and a colorful root bag. Opposite it, a five-paneled painting of mountain landscapes spans the length of a wall. This art was given to the school at its re-naming ceremony last fall by Joey and James Lavadour. Renowned artists, brothers and Walla Walla members of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indians, the Lavadours are two of Letitia Carson’s great-great-great-grandsons.

“As a kid, I was always sitting around with the old people, listening to their stories and looking at pictures instead of out playing,” Joey tells me.

One photograph in his family’s collection, shows a striking woman in a black dress: Martha Carson, Letitia and David’s daughter. She stands with her husband, a Walla Walla and Métis man named Narcisse Lavadour, and their son. Martha married Narcisse in 1868, and her daughter from another partnership later married his brother. Both couples lived on the Umatilla Indian Reservation, where many of their descendants remain today.

Though Joey grew up knowing he had Black ancestors, this knowledge wasn’t widely held in his family. At some point, Joey explained, the older generations who’d known Martha Carson and her children stopped talking about their Blackness. “They knew, but they quieted it.” Over time, this part of the family’s heritage was largely forgotten.

As a young adult, Joey became friends with a historian who later introduced him to the findings of Bob Zybach and Jan Meranda. Joey was amazed to learn of Letitia’s accomplishments and proud to be her descendant.

But not everyone in his family shared his immediate enthusiasm. “I was bringing a new story to my parents’ generation,” Joey tellsme, and some found the news unsettling. “My father looked at me and says, ‘I’ve fought all my life because I’m Indian. I don’t want to fight because I’m Black.’ ”

“It comes from being mixed themselves—Indian and white.” Joey says. “Living on the reservation, they experienced prejudice. Not from everyone, but a little prejudice goes a long way.”

Years have passed since that moment. “Today, my family is extremely proud of Letitia and being descended of her,” Joey says. “We’re multiracial, and in being so there’s a lot of conflict involving history, you know, about what has taken place.” He tells me about his tribe’s ongoing efforts to reclaim lands lost through settlement. “It’s a difficult thing, a quandary,” he says. “You’re proud of one side of your family, although it steps on the toes of the other side.”

Joey is silent for a moment, then adds, “To me, it’s one big picture.”

When I ask the Lavadour brothers how they felt about the Legacy Project, both express ardent support. “This is the real history,” James says. “Stories of people who existed in between all the ‘History’—it’s who people are, who I am.”

LAST DECEMBER, THE LEGACY PROJECT launched a traveling exhibit about Letitia’s life with a reception at the Douglas County Museum in Roseburg. Inside, I followed a din of voices past the museum’s gift shop, where visitors can buy petrified wood and books from a box labeled “True Western Stories” (titles include: Mountain Men, Loggers and Cowboys), to a room where eight colorful panels told Letitia’s story via photographs, maps and text. The exhibit will travel across Oregon, bringing Letitia’s story to museums and community centers throughout the state.

Dozens of people milled about, nibbling snacks while examining the panels. Midway through, Gwin and Zachary Stocks from Oregon Black Pioneers gave a brief overview of the Legacy Project. Afterwards, a visitor raised her hand, explained that she worked in rangeland management and had spent time in the Soap Creek Valley. “I’d love to know where Letitia’s homestead was,” she says. “Is there a marker of some kind?”

Stocks looked at Gwin. She shook her head: “Not yet.”

The Legacy Project has accomplished a lot in four years: It compiled a digital history, organized an archaeological dig, held public events on the land, recorded and archived oral histories of contemporary Black farmers, created this exhibit. But the question of what will happen with Letitia’s land remains stubbornly unanswered.

“Whether or not we create anything there will ultimately be up to the university,” Stocks says. He hopes projects like the traveling exhibit will increase public interest and encourage OSU to enter into a perpetual use agreement with the Legacy Project partners to allow them to begin building their vision on the land. “We’re dreaming big while keeping our expectations small,” he says. “For now.”

One February afternoon, I drove once more to Soap Creek Valley to see the Carson land in the bright light of a clear day. Sunshine swept over the grasslands, and I tried to imagine the Legacy Project’s visions manifested there: A working homestead, meadows blue with camas, field crops cultivated by emerging Black farmers. Instead, I found myself captivated by the sight of the open land, by the sense of possibility such a view conjures in America, where land is deeply entwined with freedom and wealth. It’s what Black leaders advocated for upon emancipation—40 acres and a mule—and what they and many of their descendants have been repeatedly denied through exclusionary land policies. It’s what provided the carefully stewarded resources that sustained Indigenous tribes for millennia, and what many are fighting to regain today. It’s what drove thousands of settlers to journey west, and what America’s formidable agricultural industry—and the prosperity and power it generates for some—is built upon.

Here, in Soap Creek Valley, these strands of history are threaded together through the same 320 acres of prairie. Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that the Legacy Project has thus far encountered more quandary than ease in its attempt to create a different future for this land. A cloud passed over the sun, and the valley fell into shadow. I thought of what Joey Lavadour says when I asked if he had a particular vision for the future of his great-great-great-grandmother’s land. “I just really love that her story is getting out there,” Joey says. “I didn’t realize, years ago, that it would mean so much to so many different people.”

This story was first published by High Country News and is reprinted in Barn Raiser with permission.

High Country News is an independent magazine dedicated to coverage of the Western U.S. Subscribe, get the enewsletter, and follow HCN on Facebook and Twitter.

Jaclyn Moyer lives in Corvallis, Oregon, with her partner and two young children. She is the author of On Gold Hill, forthcoming from Beacon Press in 2024.

Have thoughts or reactions to this or any other piece that you’d like to share? Send us a note with the Letter to the Editor form.

Want to republish this story? Check out our guide.

More from Barn Raiser

For Rural Students, Going to College is Not Easy