This is the fifth installment of Barn Raiser’s 2024 election coverage series “Charting a Path of Rural Progress,” which features interviews with rural policy experts and organizers who came together in Omaha, Nebraska, in 2023 to forge a rural policy platform on which candidates can run—and to which voters can hold their elected leaders accountable. The platform that grew out of that Omaha meeting, A Roadmap for Rural Progress: 2023 Rural Policy Action Report, released last October, details 27 legislative priorities for rural and small town America, based on legislation that has already been introduced in Congress.

This Teachers Union Leader Wants to Turn Rural Schools Into Community Hubs

The American Federation of Teachers’ Rural Caucus advocates turning public schools into social service centers

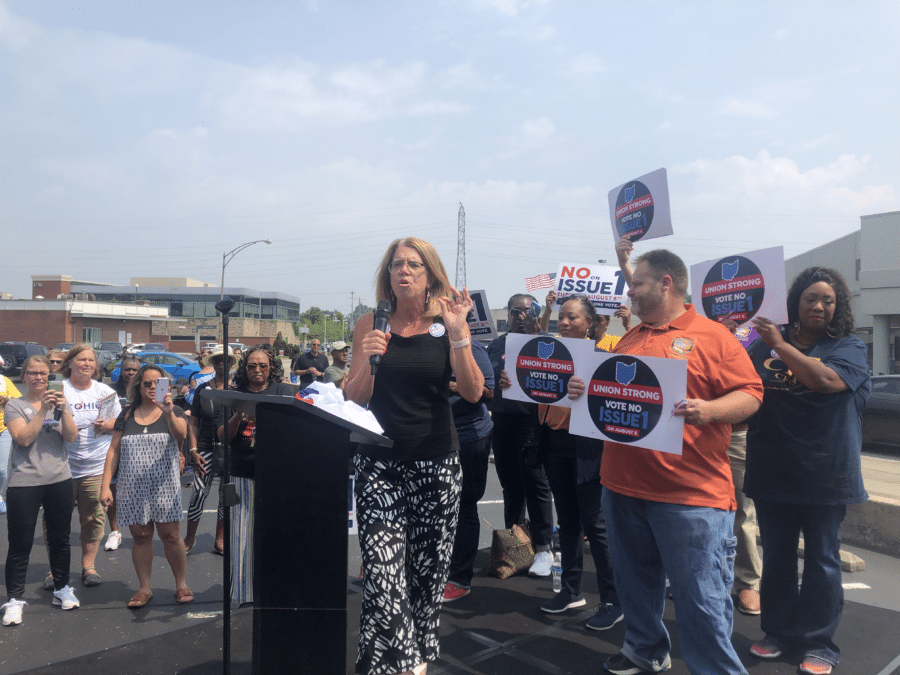

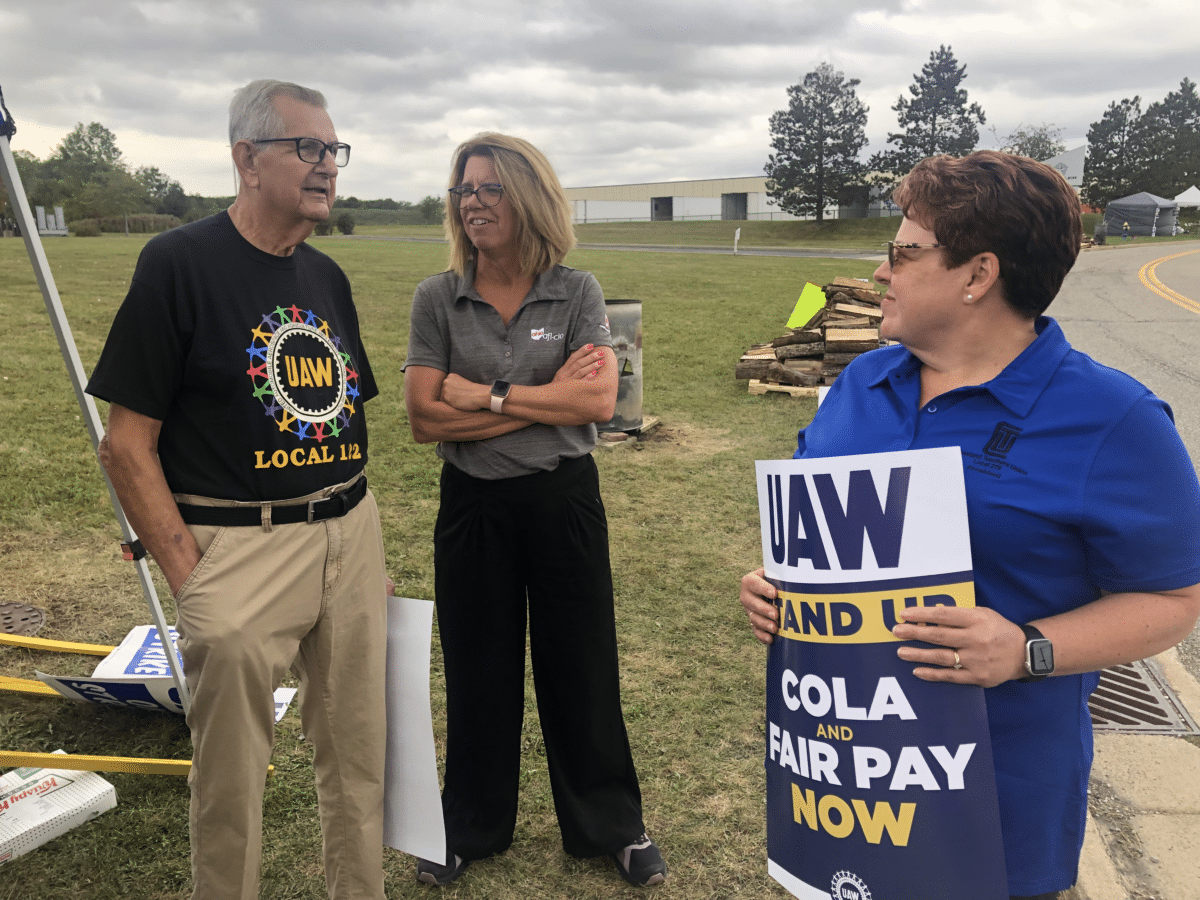

Melissa Cropper, a 58, has served as president of the Ohio Federation of Teachers (OFT) since 2012. The OFT represents 20,000 active and retired teachers in 45 school districts across Ohio and five community/technical colleges, as well as librarians and social workers. The mother of five became involved in the union while working as a school librarian in Georgetown, Ohio, a town of 4,463 about 36 miles southeast of Cincinnati.

In 2019, the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) convened a Rural Task Force to identify ways to connect with union members who live in rural areas or small towns. As a continuation of that work, Cropper is working with the AFT to establish a Rural Caucus within the union. Cropper represented the AFT at the Rural Policy Action Summit in Omaha in April 2023, which became the basis for the Rural Democracy Institute’s Rural Policy Action Report.

“We know that in our small towns and our rural areas, everything’s connected,” says Cropper. “It’s critical that we are all on the same page together and pulling for each other.”

How did you get involved with the Ohio Federation of Teachers?

One day in the early 2000’s in Georgetown, Ohio, our principal made a comment that we should not expect our students to perform as well as students in nearby Indian Hills, a wealthy Cincinnati suburb, who had more opportunity.

The comment really offended me. She was talking about my kids and my friends’ kids. I knew that our teachers had ideas about how we could do things better, but they weren’t given the opportunity to see their ideas put into action. So I ran to become president of our local union, the Georgetown Federation of Teachers, in 2005 and started advocating at a local level.

What is the AFT’s Rural Caucus?

The Rural Caucus is a structure we are using to bring our rural members together to discuss

common problems and lift them up within AFT’s work.

A lot of our rural locals are smaller, so they don’t have the finances to be able to do things like attend national conventions or any of the conferences that we have. So we’re trying to figure out ways that the Rural Caucus can help them do that.

More importantly, it’s a way to make sure that the AFT understands the issues at a rural level. AFT historically has been known as an urban-based union. But one-third of the local unions are in rural or small towns. We are trying to understand what their issues are, what their communities are like and how they can connect with other community members around the issues that are important to them.

Rural schools are the hub of the community. In rural areas the school is often where people gather, so we want to connect with our rural members on issues that are important to them, and to connect them with other people working on rural issues in an expansive way—understanding what’s happening with farmers and how we can support farmers, what’s happening in small businesses in rural areas, and how they connect with people who are working on small business issues.

In these small towns, everybody knows everybody. And when people are suffering in one area, it’s going to have an impact on our schools also.

What are the challenges facing rural educators, schools and communities, and how is the American Federation of Teachers addressing them?

Our children and our teachers are facing more and more non-academic stressors all the time. In rural areas, there’s not as much access to people who can help with health problems, social problems or mental health problems. AFT advocates for a community learning center model that places resources within the school to make those resources more accessible to students and families.

We’re also doing some work around social media and how it affects children. As part of our Real Solutions for Kids and Communities campaign, the AFT partnered with the American Psychological Association, ParentsTogether, Fairplay and the student-led group Design It for Us to confront the social media companies that have shirked their responsibility to protect kids.

Our report (“Likes vs. Learning: The Real Cost of Social Media for Schools”) outlines specific, straightforward steps the social media platforms could do today to keep kids safe and protect learning environments. It makes clear that social media companies like Meta have a responsibility for the products they release to market. They have an obligation to protect young people, not prey on them for profit.

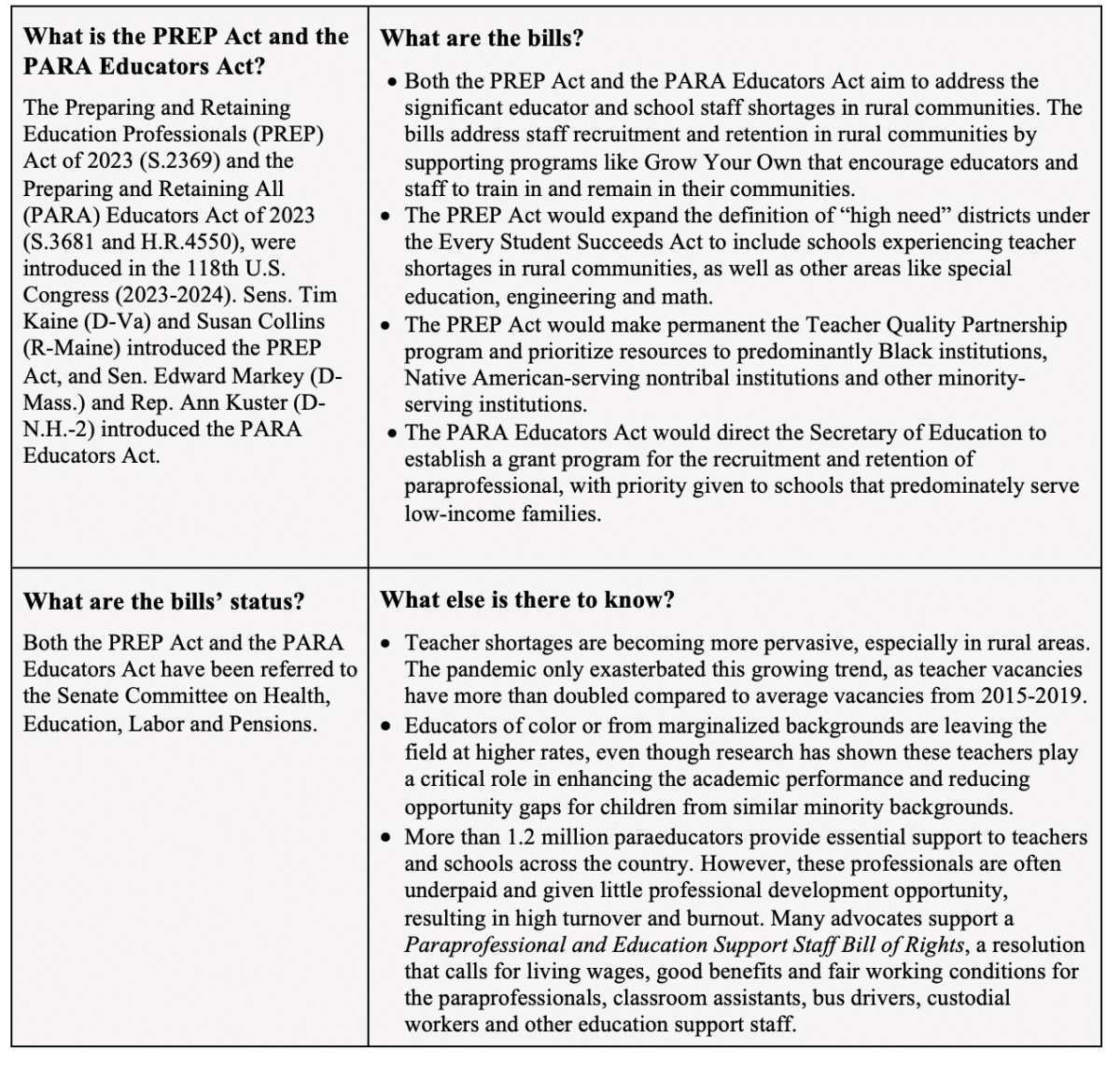

Two of the education-related legislative priorities named in the Rural Policy Action Report are passage of Preparing and Retaining Education Professionals (PREP) Act and the Preparing and Retaining All (PARA) Educators Act, both of which identify teacher recruitment and retention in rural schools as a major problem, and Grow Your Own initiatives as one solution to encourage teachers to work in their local communities. Why are these bills important?

Recruitment and retention of teachers is a big issue. AFT has been instrumental in supporting those bills and supporting programs like Grow Your Own, which those bills will fund. It’s hard to recruit people to work in schools anywhere, not just rural schools. AFT is addressing this by focusing on improving the teaching and learning environment in schools on the retention side, and by establishing programs like Grow Your Own.

These are locally based programs that target candidates, often paraprofessionals, and assist them with the funding and mentoring they need to complete the requirements to become teachers. Students benefit from having teachers who already have had experience in their schools, who know the area and who are committed to a career in education. We’re trying to establish training programs at the high school level to get students interested in teaching as a profession and to stay in their community to teach at local schools.

State lawmakers in places like Oklahoma, Iowa and Wisconsin, have been seeking ways to turn over funds for public education to private and religious (Christian) schools. So-called school vouchers are promoted as providing choice in rural areas so that people don’t have to travel as far. What is your position on such initiatives?

We’re seeing privatization across the board, not just in education. But certainly, we’re focused on education. Ohio just became a universal voucher state, which means that school vouchers are available to all students in the state. Republican legislators in Ohio are now looking at how they can use capital funds to start building private schools in rural communities, which would be very detrimental.

It’s another way of tearing down our public education system. It drains resources from our public schools. The right wing wants to see this privatization happen. All these culture war issues are being used to attack our public schools. More and more politicians are telling a negative story about our schools and using culture war issues to divide us rather than unite us. And privatization is another way to divide us along lines of race and socioeconomic status.

If our children are not learning how to work together in a public K-12 system, then that expands into adulthood. As our schools get privatized, those divides will expand into other areas also.

You mentioned that OFT supports turning schools into community learning centers. What does that involve?

We call them community learning centers, because in Ohio, community schools are charter schools. So I tend to use different language than what the rest of the country uses.

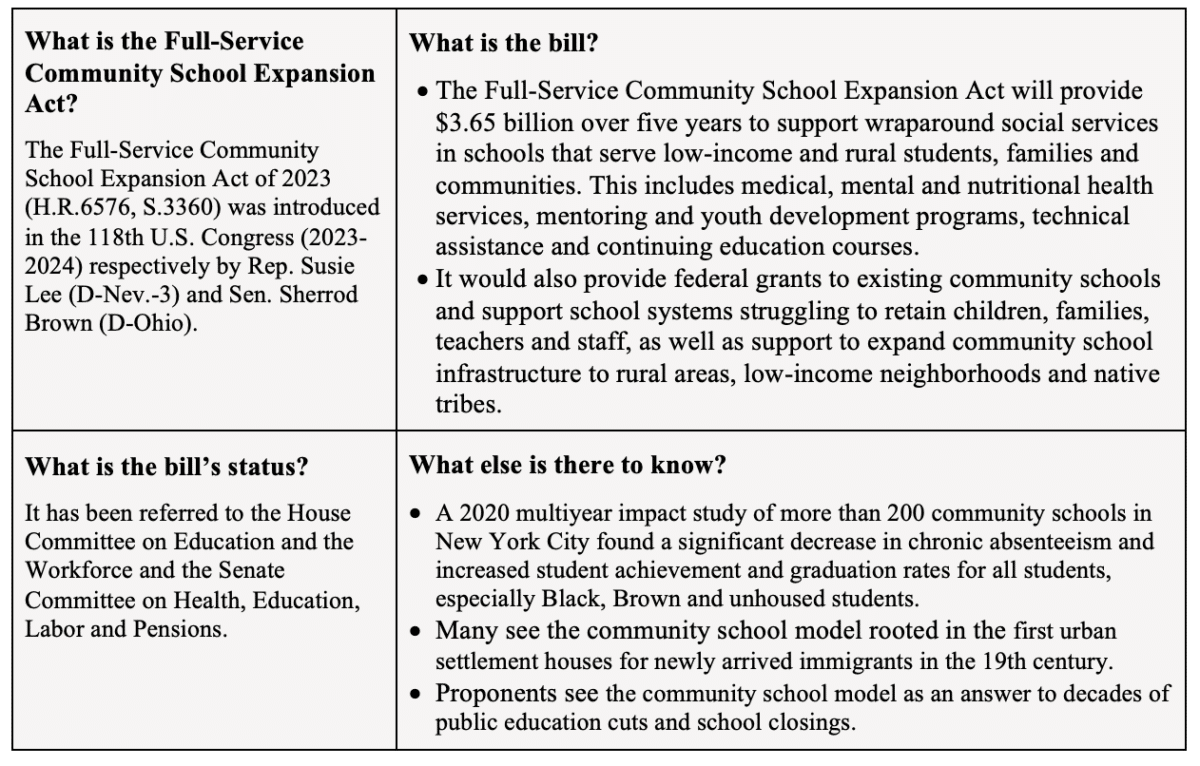

Recently, we have been advocating for the Community Schools model, which has worked really well in urban areas like Cincinnati and New York.

The Community Schools model basically means approaching schools as community social centers—places where you locate the various resources available in the community within a school. So, if a community has mental health services, behavioral health services or vision, dental, general and physical health services within a school, then children can more easily take advantage of those services. The positive effect almost quadruples if those services are also made available to families.

We want to look at how we can bring Community Schools to rural areas in order to make sure that we’re making services available and accessible so that all members of the community can benefit from them. For example, in our New Lexington School District, they are partnering with Genesis Health to build a health clinic onsite, including a dialysis lab, that will not only serve the community, but will also be used as a training ground for students working towards health care credentials. Instead of having to drive a half-hour to 45 minutes or an hour to get to a doctor’s office, rural folks would be able to access those services without taking their kids out of school or taking off work for a whole day to do it.

This is really important to us. Ohio’s Senator Sherrod Brown has been highly instrumental in supporting the Full-Service Community School Expansion Act. This bill would allow for social services to be put in schools and it would help schools build out those programs and make them accessible to students and all members of the community.

Has the community learning center model received any pushback in Ohio?

We’ve had people accuse it of being socialism or something like that. But when they look at how it actually works, most people, even some diehard Republicans, see it as being an effective and efficient use of the dollars that are already out there.

How do you handle the question of home schooling in rural areas?

To be clear, we’re not opposed anyone’s choice to educate their children however they want to educate their children. The question is: how is that education funded? There are a limited amount of dollars, and we’re already not funding our schools at the level they need to be funded. If we continue draining those resources, that’s going to hurt our public schools.

We should be investing money in our public schools and making all public schools the top choice for people, making them places where people want to be, where they want their children to be.

AFT is working hard on what we call experiential learning and workforce development. We have a project going on in New Lexington, Ohio, which is a small town about an hour east of Columbus, where they’re focusing on workforce development to make sure that students have exposure to different types of careers and that they are developing skill sets that can be used in a variety of ways.

For example, IBEW [International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers] established a pre-apprenticeship program in New Lexington. It will qualify as a year’s worth of experience in the journeyman program, and let students get into a job right away.

Our rural areas have a lack of professionals in the trades, from electricians to plumbers. We want to give students multiple ways to use these skills, whether they want get into union work or start their own business.

How do you see AFT using the Rural Policy Action Report?

AFT plans to share the Rural Policy Action Report with our members to show them what other rural-focused groups are doing and to try to help our leaders at the local and state levels meet with people in the Rural Democracy Initiative network so that we can push together in the same direction. We will use this as an opportunity to help others understand what’s happening to teachers in rural schools and our healthcare workers in our rural hospitals. We are organizing around the legislative proposals outlined in the report beyond healthcare and the K-12 agenda that help our members who live in rural spaces.

Turning to politics, what do you think of the Sherrod Brown and Bernie Moreno race for U.S. Senate? Is OFT involved?

I think that Moreno is the best candidate for Sherrod Brown to run against. There’s such a huge difference between them. Brown has always been on the side of working people. He is a champion of labor. So, yeah, he’s a top priority for us. I can’t imagine any union not endorsing Brown in this race.

What about your other senator, J.D. Vance, author of Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis?

The pretender. The person who pretends like he understands the problems that rural Americans are going through.

I’m sure he had a difficult childhood. I read his book. But he’s doing nothing to help working class families. He’s not out there listening to working class people, hearing what their problems are. He’s been tone deaf. He’s just another one who falls in line with whatever Trump says, without paying attention to the people who put him in office.

Joel Bleifuss is Barn Raiser Editor & Publisher and Board President of Barn Raising Media Inc. He is a descendent of German and Scottish farmers who immigrated to Wisconsin and South Dakota in the 19th Century. Bleifuss was born and raised in Fulton, Mo., a town on the edge of the Ozarks. He graduated from the University of Missouri in 1978 and got his start in journalism in 1983 at his hometown daily, the Fulton Sun. Bleifuss joined the staff of In These Times magazine in October 1986, stepping down as Editor & Publisher in April 2022, to join his fellow barn raisers in getting Barn Raiser off the ground.

Justin Perkins is Barn Raiser Deputy Editor & Publisher and Board Clerk of Barn Raising Media Inc. He received his Master of Divinity degree from the University of Chicago Divinity School. The son of a hog farmer, he grew up in Papillion, Neb., and got his start as a writer with his hometown newspaper the Papillion Times, The Daily Nebraskan, Rural America In These Times and In These Times. He has previous editorial experience at Prairie Schooner and Image.

Have thoughts or reactions to this or any other piece that you’d like to share? Send us a note with the Letter to the Editor form.

Want to republish this story? Check out our guide.

More from Barn Raiser

Barbara Damrosch’s Life in the Garden