This is the seventh installment of Barn Raiser’s 2024 election coverage series “Charting a Path of Rural Progress,” which features interviews with rural policy experts and organizers who are members of the more than 30 organizations that gathered in Omaha, Nebraska, in 2023 to forge a rural policy platform on which candidates can run—and to which voters can hold their elected leaders accountable. The platform that grew out of that Omaha meeting, A Roadmap for Rural Progress: 2023 Rural Policy Action Report, released last October, details 27 legislative priorities for rural and small town America, based on legislation that has already been introduced in Congress.

Organizing Rural and Small Town America for Affordable Housing and Racial Justice

Affordable housing is among the top issues for rural Americans. For this organizer, it’s also the starting point for building strong communities.

In March, the Rural Democracy Initiative conducted a wide-ranging survey of rural and small town voters that found the number one issue for people was rising costs, particularly the cost of buying a home.

When asked if the rising cost of housing preventing people from buying homes was a major or minor problem where they lived, 68% or respondents said it was a major problem, including 64% of Democrats, 71% of Independents and 68% of Republicans.

That comes as no surprise to Jaime Izaguirre, a housing organizer in Dubuque, Iowa, for Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement. Not only is the cost of buying a house beyond the reach of many, finding an affordable, well-maintained apartment or house or mobile home to rent is increasingly difficult in rural and small town America. According to the Housing Assistance Council’s 2023 report Taking Stock:

- One quarter of all rural households spend more than 30% of their monthly income on housing. More than 40% of those are renters.

- Of those rural renters who spend more than 30% of their income on housing expenses, nearly half of them spend more than 50% of their income on housing.

- Rural renters of color are the hardest hit.

In light of this crisis, it’s no surprise that Iowa CCI, part of the People’s Action organizing network, has designated housing one of its six issue areas, pledging to “organize and build power for a more just and equitable housing system across the state.”

Izaguirre grew up in Muscatine, Iowa, a town of about 24,000 on the Mississippi River, just south of Davenport, to parents of Mexican descent. Barn Raiser spoke to Izaguirre about the Biden administration’s latest affordable housing initiatives around mobile homes and how organizing for housing connects people across differences.

How did you get into organizing?

I went to Drake University in Des Moines four blocks away from the Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement (ICCI) office. A lot of my friends were very deeply impacted by racist happenings on campus. I became an organizer in college around housing and racial justice. And from that, I met some really awesome mentors at ICCI and learned a lot more about organizing and I picked up some of the needed skills to do what I’m doing now.

When I moved to Dubuque in September 2022 as an ICCI organizer, I went around and asked people: “What would you like to change about your community? What are your top three things?”

Housing came up in almost every conversation, either about the person’s home that they own, about housing in the community or about the status of certain buildings, like the dilapidated buildings with iconic facades that have fallen into disrepair. They are a good indicator of what it’s like in these Mississippi River towns that were once booming. It’s not the case anymore. You’ve got these old, beautiful buildings that are falling into disrepair.

In the case of Dubuque, the oldest town in Iowa, certain old buildings are now a source of community regret or sadness. There wasn’t any investment in these buildings for a good 40 or 50 years, so now they either have to be reconstructed entirely or are at threat of being torn down. We are losing an old brewery, the Dubuque Brewing and Malting Company which was built in 1896, and is now being demolished.

It seems symbolic of the economic hardship people are experiencing in these old river towns and across rural and small town America.

Especially around housing too, right?

We’re in this new stage of housing organizing where governments realize that housing development is key and integral to economic development. In Dubuque, we need housing just as much as we need good jobs. They go hand in hand. We have a housing shortage here, just like many other areas across the country.

Dubuque is unique in the sense that it’s population has grown. But it’s a question of the status and condition of the housing that exists. A lot of homes in Dubuque have been bought up by investors. And landlords don’t treat these places with the sense that they are a home. For them, it’s a business strategy.

One of the biggest problems with Dubuque is that you’ll be lucky to find somewhere to rent for less than $800 that is decent. And to have a landlord that’s responsive to your needs, with a maintenance crew, well, that would be pretty top-tier. And so a lot of our organizing here has been focused on delivering fairness as part of progress. And asking for mixed income housing as a part of new developments.

So we’ve created a five point platform that we’re organizing from.

The first point is around pest control. This is about creating fairness around cost responsibility. We’ll see an infestation in a building where three, four or more tenants have a bedbug infestation, and the landlord is trying to charge one tenant for the cost of this pest control without any proof that they caused the infestation.

The second one is around expanding number of rental inspectors in the housing department, whose job is to investigate complaints from residents and also to perform routine inspections of rental properties. Dubuque has a little over 11,000 rental units and does a little over 2,000 inspections a year. That means it’s going to take five years for inspectors to get back to a property after they’ve inspected it. We’re trying to expand the number of inspectors within the housing department.

The third thing that we’re working on is application fees. We’re trying to get rid of application and processing fees for prospective tenants. This would exclude credit and background checks, which we want to cap at $20.

Fourth, we’re working on educating tenants. One of the options that we’re looking at is public service announcements to renters about their rights, which is pretty common in places like Chicago and New York. And then we’re looking at providing each tenant with a booklet on their rights as part of signing a lease.

And then the fifth point is advocating for mixed-income housing development.

And then, from time to time, we also challenge local slumlords.

ICCI is figuring out what it would look like to expand organizing around housing issues. A lot of rural counties and small towns don’t have their own inspection programs. They’re relying on either the state government or an intergovernmental association, so there’s very little oversight or accountability for landlords and business practices.

The more that I organize, the more I realize there’s tons of resources and programs out there. It’s just that they’re not designed for the people that they should be benefiting. It’s always for developers, or corporations or in some cases nonprofits, which are often not in rural areas.

The Biden administration has made development of affordable housing one of is priorities. On March 21, the White House released a raft of economic policy proposals, which included a chapter devoted to federal policy solutions that would increase the supply of affordable housing. Is the administration backing up its words with action?

One of the strongest things that has happened under the Biden administration involves mobile homes. In February, HUD (Department of Housing and Urban Development) established the Preservation and Reinvestment Initiative for Community Enhancement (PRICE) Program, which is a first-of-its-kind initiative to invest in mobile home parks, either through direct assistance to residents, or in park infrastructure and improvements. And that is huge.

Here in Dubuque we’ve been organizing a trailer park, Table Mount Mobile Home Park, which is now owned by an absentee landlord, Impact, a Colorado-based company. In 2017, when the park was purchased they were renting out lots at $230 a month. Now it’s $530 a month. So that’s the issue with the corporate landlord. They diminish services, discontinue maintenance and improvements and they increase charges.

It all goes back to 2008 when the crash happened in the housing market. At the time, the federal government was trying to think through how they could support affordable housing initiatives. And they looked to mobile homes as a vital resource for affordable housing in rural America.

So, the Obama administration authorized Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae under the Federal Housing Finance Agency to use federally financed loans to boost the mobile home housing market and promote mobile homes as an affordable housing option. But then private equity investors caught on to the fact that this was a very cheap and easy way to acquire start-up capital. So they created corporations to get these loans, buy up trailer parks, and turn the residents of these parks into cash cows.

It was one of the biggest missteps in the post 2008 crash. We looked to boost and support affordable housing options by giving money to corporations, and they’ve made us pay for that every step of the way.

The approach of the Biden administration’s PRICE Programs is to put money directly into the hands of residents and allow residents to make their own decisions for how to best to improve and maintain their trailer park. It is a much better approach to the problem than giving equity firms the capital to buy a park.

Later this month there is going to be a public hearing at the Dubuque City Council regarding an application that’s going to be submitted for PRICE funds. Ideally, we’ll get the funds necessary to help residents purchase the Table Home Mobile Home Park and create a resident owned community, or it will go to a nonprofit to buy the park and run it as a public good. But, that being said, the program only has about $235 million in funding, so it’s gonna be pretty competitive.

Are you organizing in other places besides Dubuque?

We are working with folks organizing in 10 different parks—in Davenport, Cedar Rapids, Cedar Falls, Des Moines and here in Dubuque. And on May 20 we are meeting at five different satellite locations with the Federal Housing Finance Agency to ask them to take action on the private equity-owned trailer parks that were financed by Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.

How does organizing around housing translate into a political agenda?

This is the struggle of being a community organizer: the way to win on any issue is not always the organizing way. A lot of people will start with the people who have money and access to power who are already organized and represented. But when we work with everyday people, we start with much less and we have to build power up ourselves from the grassroots.

There are different ways to view the housing issue. Renters don’t see housing as an economic development issue. Their view of the issue centers on the fairness aspect, that they should have decent housing even if they’re not making enough money to pay $1,200 in rent and still be below 30% of their income on housing costs.

The first step in organizing around housing in places like Dubuque is building up the power of our own group and a clear consensus of what it is we want. Then, we can start engaging other people: city counselors, developers, bankers and all sorts of stakeholders to do the negotiating and politicking with.

In your work in Iowa, do you sort see any connections between racial justice and housing?

Housing is a racial justice issue. So much of how spaces are constructed comes down to what is affordable and what isn’t. And there’s more affordable housing in certain areas of a region or a city. And if you factor in socioeconomic status and histories of redlining, it becomes really apparent that solely market rate housing or housing that doesn’t benefit all income levels is a racist practice. It’s economic segregation and a continuation of the history of redlining.

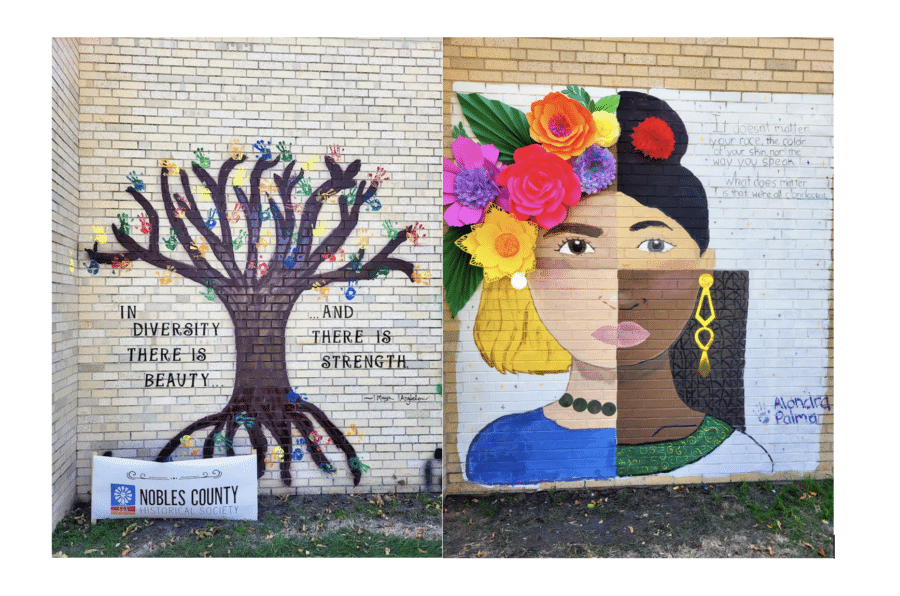

Whether you’re black, brown or white, if you make a decent amount of money, housing is not an issue. But it’s issues like housing that have really connected a lot of people in Dubuque. We hear it all the time at ICCI: “This organization, they’re different, they’re kind of weird, because in no other group would I see these people in the same space as me. I would have never interacted with this person had it not been for ICCI.”

And I think that’s how community should be built, right? We should be interacting with people that don’t look like us, that don’t think like us. And that’s the beauty of constructing community, creating those connections.

Joel Bleifuss is Barn Raiser Editor & Publisher and Board President of Barn Raising Media Inc. He is a descendent of German and Scottish farmers who immigrated to the Upper Midwest in the 19th Century to become farmers in Wisconsin, Minnesota and the Dakotas. His grandmother was born in the Scottish Highlands to parents listed in the Census of Great Britain, 1881 as “farm servants” on land owned by the Duke of Fife. Joel himself was born and raised in Fulton, Mo., a small town on the edge of the Ozark Highlands. He got his start in journalism in 1983 as a feature writer and Saturday reporter/photographer for his hometown daily, the Fulton Sun. Bleifuss joined the staff of In These Times magazine in October 1986, stepping down as Editor & Publisher in April 2022, to join his fellow barn raisers in getting Barn Raiser off the ground.

Justin Perkins is Barn Raiser Deputy Editor & Publisher and Board Clerk of Barn Raising Media Inc. He is currently finishing his Master of Divinity at the University of Chicago Divinity School. The son of a hog farmer, he grew up in Papillion, Neb., and got his start as a writer with his hometown newspaper the Papillion Times, The Daily Nebraskan, Rural America In These Times and In These Times. He has previous editorial experience at Prairie Schooner and Image.

Have thoughts or reactions to this or any other piece that you’d like to share? Send us a note with the Letter to the Editor form.

Want to republish this story? Check out our guide.

More from Barn Raiser

Harvesting Destruction