Hear me out, it’s a serious question: What do laundromats tell us about what it means to build community and movements for justice? The thought hit me one day when in the middle of a recent cold snap, my family’s dryer stopped working, making me haul my family of five’s eight loads of laundry to the Laundromania up the street.

Between loads, I noticed a woman arrive who, despite looking visibly exhausted, managed to carry two large clothing bins that engulfed her tiny frame. After she put her clothes in the wash and settled in, we managed to strike up a conversation. I’ll call her “Dolly.” Dolly told me that she had come straight from her shift at a local Kum and Go gas station where she works as a cashier. She had a neighbor drop her off because it was too cold to walk in the subzero temperature of minus 30 degrees.

Dolly shared that doing laundry, though necessary, cost “a lot” these days. I discovered this when, after eight loads, the total came to about $60 (which didn’t include what I spent on detergent and dryer sheets).

Though our conversation was brief, I realized it confirmed what the late, great author Barbara Ehrenreich argued over twenty years ago in Nickel and Dimed: it is expensive to be poor in the United States, and working-class people pay the most for basic services and goods.

Indeed, I am not the first to observe the ever-widening stratification of wealth in our society, but I am struck by the callous and cynical nature of state officials nowadays who seek to punish people because they are poor. Take, for example, Iowa’s rejection back in December of a federal program that gives $40 per month for each child in a low-income family to buy food. The federal government asks states to pay for half of the administrative costs of the program, or an estimated $2.2 million in the first year for Iowa and $1.3 million in subsequent years. Gov. Kim Reynolds joined 14 other GOP-led states in declining assistance from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Summer Electronic Benefits Transfer for Children (Summer EBT)—deemed essential to approximately 240,000 children across Iowa—saying the program was “not sustainable” and that EBT cards were responsible for perpetuating childhood obesity. With a state budget surplus of nearly $2 billion—the result of underfunded public priorities and tax dollars stowed away to cover budget holes created by tax cuts that primarily benefit the wealthy—Gov. Reynolds signaled that she does not trust low-income families to make their own decisions, and they should suffer as a result.

There’s no mistaking the parallels between Gov. Reynold’s decision and the nativist, retribution-fueled rhetoric that has taken over the state’s Republican party and its presidential candidates, targeting the administrative state and our democratic institutions alike. Anyone near a television screen or radio in Iowa over the past few months has seen a state where vitriolic language is embraced as the American way. The coincidence of this year’s Iowa Caucus with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day elevated just how much this rhetoric is out of step, symbolically and strategically, with the language of civil rights and faith-led movements for racial, economic and social justice.

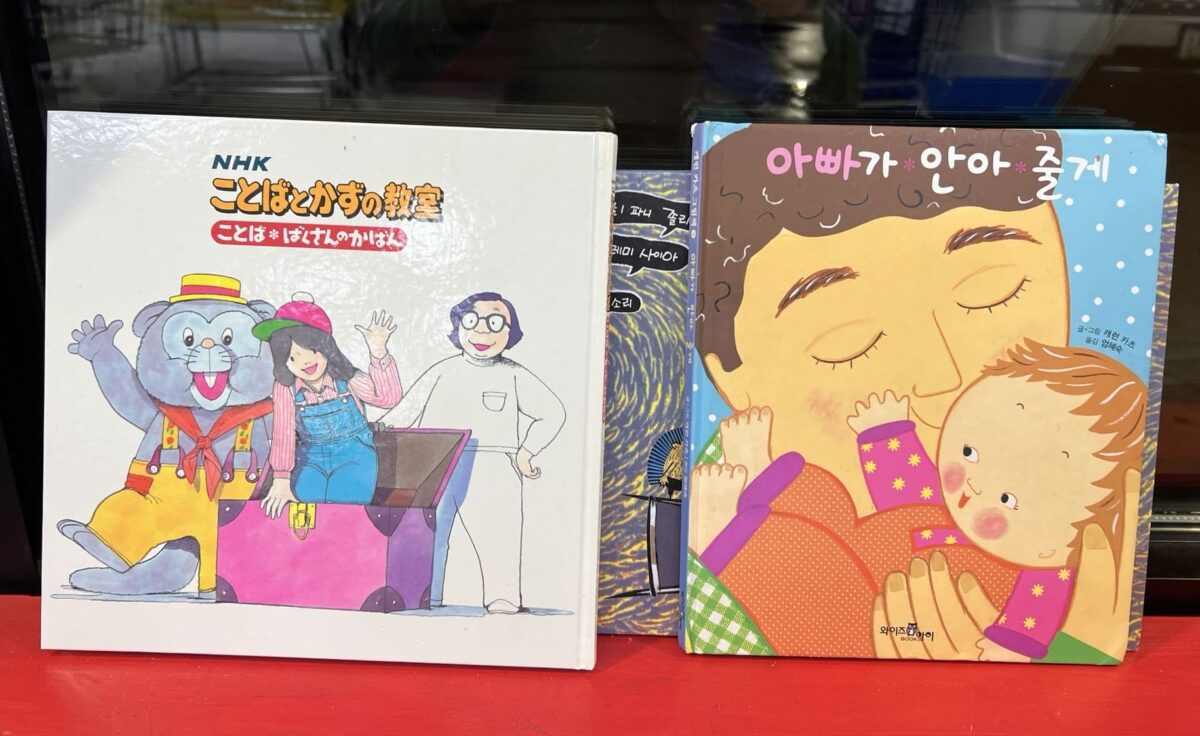

It was a dissonance similar to that between the cringe-worthy political commercials that I watched skim across my screen over the past few months, and a second chance encounter I had at the laundromat with a neatly ordered and cheerful stack of children’s books in various languages: Chinese, Spanish, French, Japanese. Like this tidy stack of books, the laundromat reflects the diverse languages and peoples who live nearby. It is a clean and well-ordered place, one where Congolese, Sudanese and Central American immigrants mix among Black and White families, everyone doing the ordinary, mundane tasks of caring for themselves and their loved ones.

As I ponder Dr. King’s legacy for today, I am acutely aware of the ongoing divisions in our society. In his final speech given on April 3, 1968, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” to support striking sanitation workers in Memphis, he meted out a powerful critique of both economic injustices that kept poor people poor and discriminatory business practices. King’s message remains as urgent as ever.

I’ll admit that even for me, a perennial optimist who desperately wants to see bridge building across political aisles, it can be hard to stay hopeful about the future of American democracy. After his victory in the Iowa Caucuses and win in New Hampshire, Donald Trump—the twice impeached, four-time indicted ex-president accused of plotting to overturn the 2020 election, liable for sexual assault and defamation to the tune of over $80 million and his family business guilty of rampant tax fraud—remains the Republican front-runner.

Still, I remain hopeful. Why? Because everywhere I look—at least, when I’m not glancing at various iterations of the outrage machine—I see people working hard, finding the courage to struggle together, striving to make the world better not just for themselves but for the people around them. People in my community, the young and the old alike, engage in everyday acts of justice, mercy and kindness. There are no false claims to “glory” proclaimed by a media or political apparatus that preaches a theology of retribution and greed. Instead, these small acts—like leaving children’s books at a local laundromat—preach an active faith, one that envisions the kind of beloved community that King sought. And perhaps, if we are to see it close enough for ourselves, it just might have the power to dispel the highly publicized and vocal outrage that swirls about us.

Kristy Nabhan-Warren is the V. O. and Elizabeth Kahl Figge Chair of Catholic Studies and a professor in the Departments of Religious Studies and Gender, Women's, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Iowa. She is the author of Meatpacking America: How Migration, Work and Faith Unite and Divide the Heartland.