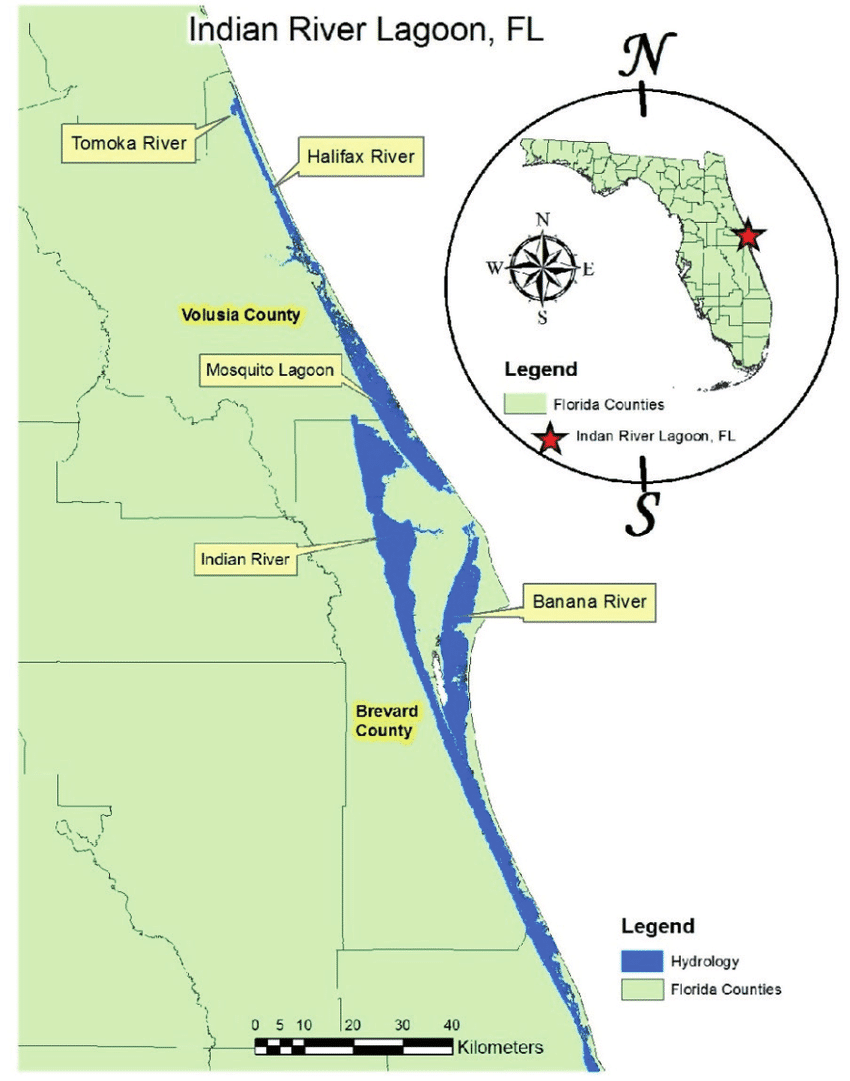

Three years ago, in December 2020, a startling number of deaths began to unfold in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon (IRL), a 156-mile grouping of lagoons on the Atlantic coast. The victims were manatees (Trichechus manatus), a federally threatened marine mammal also known as the sea cow.

Lawn Fertilizer Bans Not Solving Manatee Crisis in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon

Research from Florida Atlantic University shows sewage is a driver of harmful algal blooms

By December 2021, the mortalities pushed the statewide manatee death tally to a record-breaking 1,100, about 10% of the estimated population at the time.

Officials declared the die-off an Unusual Mortality Event (UME), a rare designation that calls for immediate response under the federal Marine Mammal Protection Act. Necropsies showed many of the animals had died of starvation. The manatees’ primary food source, seagrasses, have suffered what scientists have described as widespread catastrophic loss. (A movement of scientists and citizens are urging the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to reclassify the species as endangered. As of December 1, 2023, investigation into the UME continues, and seagrass monitoring in Mosquito Lagoon—part of the Indian River Lagoon system—shows adequate forage for the 2023/2024 winter season, according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission investigation.)

For over a decade, local lawmakers have enacted restrictions on residential fertilizer use, such as rainy season fertilizer “blackouts,” seeking to restore water quality in the lagoon. But a recent study published in Marine Pollution Bulletin shows that water quality only worsened over a five-year period of the bans, calling into question the overall effectiveness of the fertilizer ordinances by themselves, while pointing to another culprit: sewage.

The fertilizer-versus-sewage issue has been a source of debate over how to limit harmful algal blooms—or unusually high densities of algae, both macroscopic and microscopic—in the lagoon, which are caused by eutrophication. Eutrophication is the over-enrichment of human-derived sources of phosphorous and nitrogen, which are essential for plant growth but supercharge the growth of harmful algae and phytoplankton.

The blooms kill seagrasses by choking out the light seagrasses need to grow, says Brian Lapointe, lead author of the study and marine ecologist at Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. “As the blooms become more frequent and more extensive,” he says, “light becomes more diminished, and what was once a healthy seagrass meadow becomes very limited.”

Unlike algal blooms, seagrasses don’t get all their nutrients directly from the water. “[Seagrasses] have roots and rhizomes like land plants, and so ideally, they like to grow in a water column that is relatively low in nutrients,” says Lapointe. “They need a lot of light to grow.”

Despite the catastrophic impact of algal blooms to seagrasses, to the average observer there might not appear anything unusual about the water. “There can be subtle changes in the transparency of the water that might not be perceived by people,” says Hans Paerl, a marine ecologist at the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences, who was not involved in the study.

Humans have doubled the amount of nitrogen in the land-based nitrogen cycle with an industrial process that transforms atmospheric nitrogen into fertilizer, and a large portion of this excess makes its way into waterways, so at first, fertilizers seemed like the likely cause of eutrophication in the lagoon.

Starting in 2013, six counties that encompass the lagoon (Volusia, Palm Beach, Brevard, Indian River, St Lucie, and Martin) instituted or expanded fertilizer ordinances in an effort to combat eutrophication.

To assess the impact of the fertilizer ordinances, Lapointe and co-authors measured the concentration of nitrogen both in the lagoon’s water and the tissues of macroalgae a year before and four years after the bans took effect. Their methodology used nitrogen isotope ratios in the macroalgal tissues pre- and post-ban to determine the origin of the nitrogen.

What they found was dismaying.

“It was clear to us that these fertilizer ordinances were not having the positive effect that was expected by many, many people,” says Lapointe. Four years after the ban’s inception, nitrogen concentrations were higher. In the northern segments of the lagoon, wet seasons post-ban had higher ammonia, nitrate, and total dissolved nitrogen concentrations, all of which can cause eutrophication.

Anticipating the possibility this might be the case, the authors had also measured nitrogen isotope ratios in the macroalgal tissues pre- and post-ban—a methodology meant to determine the origin of the nitrogen, and they found it wasn’t fertilizer. “The fact that we saw these isotope values go up, become more enriched, rather than go down, meaning more depleted, clearly pointed to human waste as the nitrogen source fueling those blooms,” says Lapointe.

Three hundred thousand septic tanks drain into the lagoon, according to Lapointe. “When these very low elevation areas flood, those septic tanks and drain fields are underwater. All that stormwater coming off into the lagoon is carrying human waste.”

“Even though fertilizers are being reduced, which is a good thing because that means the total amount [of nitrogen being discharged] is going down, a large proportion of that total amount is still sitting in the septic systems that are putting nitrogen into the system,” says Paerl.

Lapointe says that other areas in Florida, like Tampa Bay, have experienced development booms in recent decades without catastrophic seagrass losses. “They had adequate infrastructure to clean up their sewage,” he says. The results of this study have clear implications for restoring the manatee’s main food source, said Lapointe. “We need to do a better job of keeping human waste out of the water.”

Emily Shepherd is a freelance writer covering science, including wildfire and wildlife conservation. She worked in wildlife conservation for eight years, followed by two years fighting wildfires as a U.S. Forest Service hotshot. Her work has appeared in EOS, Undark Magazine, and Terrain.org. Find her on Twitter @emilyshep1011.

Have thoughts or reactions to this or any other piece that you’d like to share? Send us a note with the Letter to the Editor form.

Want to republish this story? Check out our guide.

More from Barn Raiser