This is the fourth installment of Barn Raiser’s 2024 election coverage series “Charting a Path of Rural Progress,” which features interviews with rural policy experts and organizers who came together in Omaha, Nebraska, in 2023 to forge a rural policy platform on which candidates can run—and to which voters can hold their elected leaders accountable. The platform that grew out of that Omaha meeting, A Roadmap for Rural Progress: 2023 Rural Policy Action Report, released last October, which details 27 legislative priorities for rural and small town America, based on legislation that has already been introduced in Congress.

This Montana Rancher Has a Beef with Corporate Meat Monopolies

For Gilles Stockton, antitrust enforcement is they key to revitalizing our food system and fractured politics

Gilles Stockton is a third-generation Montana rancher who lives with his second wife outside of Grass Range, Montana (population 114), where he grew up and has operated his family’s ranch since 1975.

Yet, Stockton’s deep hometown roots belie an international range to his life’s story. Stockton was born in France—his father served in the U.S. Army and met his mother, a French citizen, in the last year of World War II.

In 1987, Stockton attended the annual meeting of the Northern Plains Resource Council, where he remembers hearing a North Carolina chicken farmer explain how the effects of corporate consolidation and vertical integration in the poultry industry was coming for cattle ranchers. His warning, recalls Stockton: “Don’t let yourself become like me—a serf on my own land.”

Since then, Stockton has made it his mission to protect family farmers buffeted by agricultural monopolies and global market structures. As the former president of the Montana Cattlemen’s Association, Stockton spoke out against the policies of the “big shots” at the more conservative Montana Stock Growers Associations (an affiliate of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association) for supporting the globalization of the meat industry.

Though he claims to be “three-quarters” retired, Stockton’s continues to work with his fellow ranchers and state policymakers through the Northern Plains Resource Council around “commonsense issues”: supporting country of origin labeling requirements for beef, opposing a national identification system for cattle that relies on numbered ear tags rather than brands, advocating for reforms to the Beef Checkoff program, which, he describes as a de-facto tax that solidifies the interests and dominance of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

Stockton is a regular contributor to publications such as Western Agricultural Reporter and the Tri-State Livestock News. His first book, Feeding a Divided America: Reflections of a Western Rancher in the Era of Climate Change, culled from a lifetime of experience and research, will be published in April by the University of New Mexico Press.

This week the Biden administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture finalized a new rule around “Product of U.S.A.” labeling that would require meat producers to maintain documentation to support that claim. Previously, multinational corporations have exploited a loophole that allows them to import meat, repackage it and label it “Product of U.S.A.” What are your thoughts about the new rule, and why should people care about it?

Closing that loophole is a very good thing, but it’s something that could have happened day 1 in the Biden administration. The only reason the big meatpackers used it was to pass off imported meat as domestic. This new rule would require the label only be used on animals born, raised, slaughtered and processed in the United States.

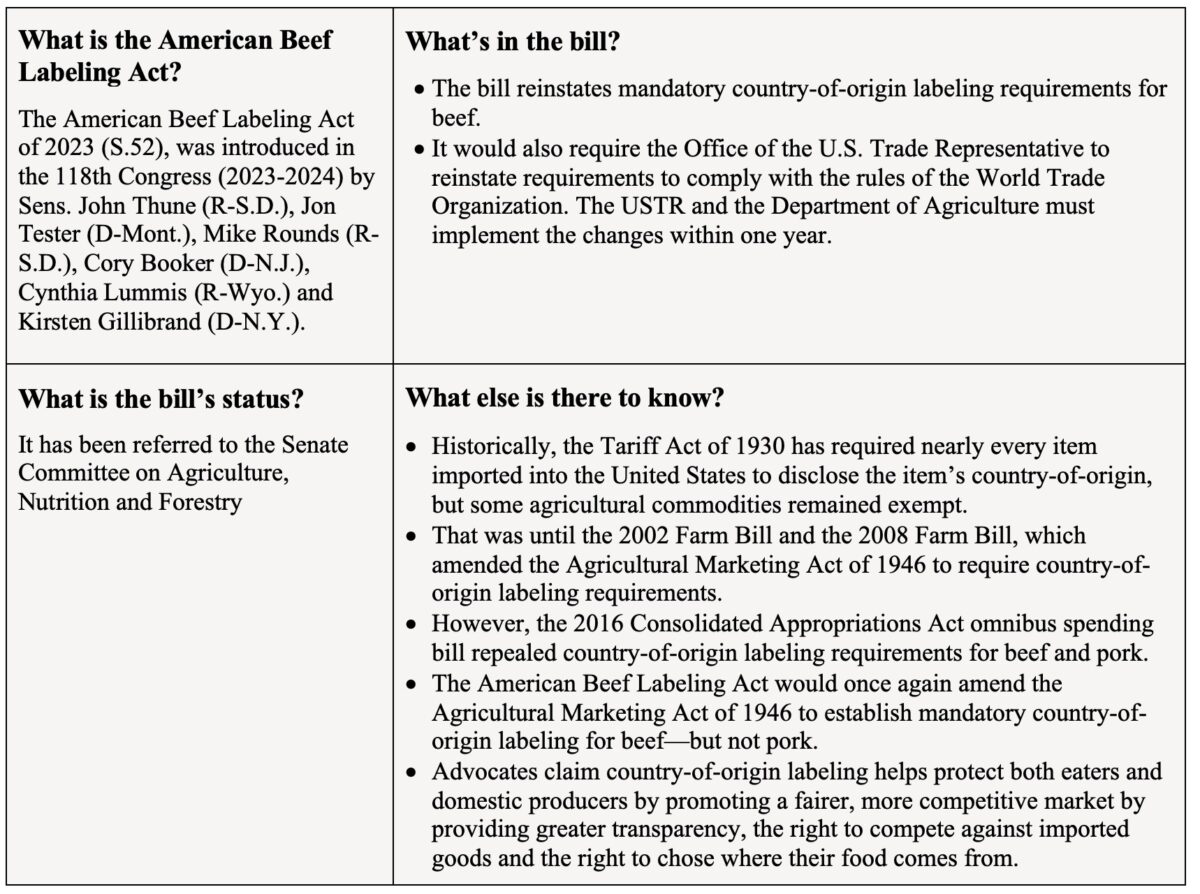

But what we still need to require country-of-origin labeling. That would require meatpackers to designate where the animal was raised, fed and slaughtered, and right now, it’s not. So, there’s still a loophole. Country-of-origin labeling and the “Product of U.S.A.” label are two different statutes. The “Product of U.S.A.” label is voluntary, and is overseen by the USDA.

But country-of-origin labeling has to be authorized by Congress and has implications in trade negotiations. Other food currently has country-of-origin labeling requirements, including lamb, seafood, poultry, grapes and nuts [established under the 2002 Farm Bill and 2008 Farm Bill]. The only exemptions are beef and pork, because the big packers are importing beef and pork, but want to pass it off as a U.S.-raised product.

When did that change happen?

A 2016 appropriations bill passed by a Republican-led Congress during the Obama administration repealed mandatory country-of-origin labeling requirements for beef and pork.

A really strong coalition has now been built around the country-of-origin labeling issue. A lot of people are starting to understand what it is. The major industry lobbyists, like the North American Meat Institute, which acts as the spokesman for the big meatpackers, argue that we can’t have country-of-origin labeling because it’s out of compliance with the WTO [World Trade Organization]. But basically both the Trump administration and the Biden administration have stopped supporting WTO. So that excuse doesn’t work anymore, and it makes it difficult for consumers to really know where their food comes from.

How does country-of-origin labeling relate to the bigger picture of how the meat industry operates today?

It adds some clarity to the market, but it doesn’t solve all the issues. We’re not going to solve the major issues until we decide to enforce antitrust laws. It was done in 1921 with the Packers and Stockyards Act, which sought to protect farmers and ranchers from monopoly power. And that was very effective for almost 50 years. But then things began to change in the 1980s when the courts narrowed the ability to enforce the Act.

Now we’ve got a global cartel controlling the industry. And at the same time, we have a cartel of retailers and grocers. We’re not talking enough about them—thankfully the proposed merger between Kroger and Albertsons has been blocked for the time being. Ramping up the antitrust efforts by the Federal Trade Commission and the Justice Department is one of the best legacies of the current Biden administration. But the issue is also bipartisan. Interestingly enough, you can still find a lot of consensus on the need for antitrust enforcement by both Republicans and Democrats.

But there are still corporatists that control the majority of both parties. Take Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.)—you can’t even get her to be a sponsor for country-of-origin labeling, even though she’s the chairwoman of the Senate agriculture committee.

What else could the Democrats do nationally and in Montana to change the dynamics?

They could have a coherent plan to revitalize rural America and revitalize agriculture.

The Democrats do not have a coherent ag policy. That was very apparent when I testified before the House Ag Committee in April 2022 on livestock issues. The guy to my right was the president of the NCBA [National Cattleman’s Beef Association] who, of course, opposed everything that I had just said. And then when the questioning time came, all of the Republican members of the committee were tossing this guy softballs. I didn’t get one softball. There was a scattering of questions, but there was no pattern to them. I got no help from the Democrats on the committee. The Republicans on the other hand were all primed with talking points. I got a scattering of questions, but there was no pattern to them.

It seemed to me that Democrats are stuck with the idea that they are the only adults in the room able to run the government, but they don’t have a good idea about what they should be doing.

In Feeding a Divided America, I make the case that the industrial model of agriculture will not be able to meet our food needs as the climate gets to be more and more uncertain. The only way to be productive in such difficult climatic conditions is to have diversified farms that are raising a little of everything. When I was a kid, everybody had, wheat and barley and milk cows and chickens and gardens and all of that. Nobody has time for any of that anymore. Around here, it’s just cattle. We have to devolve our agricultural system back to a smaller family farm system. And the way to do that is through the proliferation of markets.

What do you mean?

The market system for all of the major agricultural commodities are controlled by the global corporations. For cattle, it’s three companies: JBS, Tyson and Cargill. For grain, it’s two: Cargill and ADM. The market systems they control are not competitive. They’re proprietary markets run by and for the benefit of the global corporations. We need a proliferation of markets that are local and regional, and we’ve got to enforce antitrust laws. Our current system has ruined rural America and we probably are not going to be able to feed you in the future.

Who are the big shots in Montana’s cattle industry?

There are a few families that are constantly at the leadership of the Montana stock growers. Over the years they weave in and out from being in charge. The Montana Stockgrowers and the NCBA policies favor the global corporations that control the market for cattle.

They’re all Republican. But I wouldn’t say that explains it all. For instance, at the Montana Cattlemen’s Association—we don’t poll—at least half are probably Republican. But of those that are Republican and of those that are progressive, almost all have pretty libertarian attitudes, myself included. You know, “Leave us the fuck alone.”

If you were in charge of the Democratic Party in Montana, what would you be advocating for the party to do?

Very vocally support country of origin labeling and reform of the Beef Checkoff program. Question the validity of ear tagging all the cows. Reform the cattle market. Make the meatpackers buy their cattle through an electronic auction system instead of this under-the-table system that’s been created. And support the right to repair the farm machinery that you own. Those issues right there would go a long way to getting the attention of farmers and ranchers in Montana.

On a broader level—and this may sound off the wall to you—but the Democratic Party has got to take a stand on the proliferation of grizzly bears. I think the grizzly bear issue was one of the bigger factors for why the Democrats lost to a Republican supermajority in Montana two years ago.

What are some issues facing ranchers in Montana that people might not be aware of? For instance, are grizzly bears affecting you all?

Grizzly bears are supposed to be contained in mountain areas around Yellowstone Park and Glacier Park. But they’re migrating out because there are too many. Grizzly bears, historically, were a plains animal, not a mountain animal. So as their numbers have increased, they’ve been moving east [from Yellowstone] into farms and ranches. And if you’ve got a bunch of little kids who want to go running down to play by the creek, well, they can’t.

More and more people are having dangerous encounters with grizzly bears. Think about some suburban mother. Her son and his buddies are going elk hunting. And she worries, “Are they going to come back?” And who do they blame? They blame the Democrats even though the Democrats as a party have not taken a public position on Grizzly bear reintroduction.

So it is not so much the predation on the cattle as it is the potential threat to humans?

Well, it’s both. You’ve got bears that are wandering out of their designated areas. In some places you’re not safe to go out in your back yard at night and pee.

Are you a hunter?

I used to be. I don’t like to kill anything anymore.

Wolves are back in the upper Midwest, and they don’t attack people but they do get cattle. So that’s an issue.

Of course, wolves are part of the issue. That’s where it started. For the ranchers, it pisses us off.

So you have wolves in Montana too?

Yeah, but it’s looking like the grizzly bears are out competing the wolves, and limiting the wolves from increasing. This is especially true in Yellowstone Park where there are now only 100 wolves but 700 grizzlies.

In Montana you have a radical right seems to be ascendant in the legislature.

Oh, we sure do.

They’re not focused on anything that’s going to help anybody do anything—just keeping children with gender dysphoria from playing basketball. That’s the limit of their ideas.

At the Northern Plains Resource Council, one of the committees that we have is the Democracy Committee. We’re trying to figure out how to protect the Montana Constitution from the depredations of the right wing.

It’s a weird dichotomy here in these little towns. We work together. We help each other gather cattle. If somebody needs for me to go and bring a load of calves down from the mountains, I go. We do all that. We also, organize ourselves to run the schools, to have an ambulance service and the volunteer fire department. Everybody’s involved. But beyond the local, there is no trust at all in the government. Why is that? I’m not sure.

It blows my mind that people profess to see no significant difference between Biden and Trump. Are they insane?

Justin Perkins is Barn Raiser Deputy Editor & Publisher and Board Clerk of Barn Raising Media Inc. He is currently finishing his Master of Divinity at the University of Chicago Divinity School. The son of a hog farmer, he grew up in Papillion, Neb., and got his start as a writer with his hometown newspaper the Papillion Times, The Daily Nebraskan, Rural America In These Times and In These Times. He has previous editorial experience at Prairie Schooner and Image.

Joel Bleifuss is Barn Raiser Editor & Publisher and Board President of Barn Raising Media Inc. He is a descendent of German and Scottish farmers who immigrated to the Upper Midwest in the 19th Century to become farmers in Wisconsin, Minnesota and the Dakotas. His grandmother was born in the Scottish Highlands to parents listed in the Census of Great Britain, 1881 as “farm servants” on land owned by the Duke of Fife. Joel himself was born and raised in Fulton, Mo., a small town on the edge of the Ozark Highlands. He got his start in journalism in 1983 as a feature writer and Saturday reporter/photographer for his hometown daily, the Fulton Sun. Bleifuss joined the staff of In These Times magazine in October 1986, stepping down as Editor & Publisher in April 2022, to join his fellow barn raisers in getting Barn Raiser off the ground.

Have thoughts or reactions to this or any other piece that you’d like to share? Send us a note with the Letter to the Editor form.

Want to republish this story? Check out our guide.

More from Barn Raiser