The American justice system has long operated differently for different groups, with people of color and those from marginalized populations facing separate and unequal judicial hurdles and impacts. This stands true for Native communities, whose exclusion is little understood, whose struggles are rarely reported on and to whom the law is applied in complicated, punitive and capricious ways.

Federal Courts Sentence Native Americans to Longer Prison Terms

How federal authority over tribes fails to provide equal justice under the law

Federal charges ordinarily cover matters of national reach: immigration, voting rights, racketeering and the like. Not in Indian Country. Tribal citizens may find themselves in federal court for a wide range of allegations—not just serious crimes, such as murder, but lesser offenses, like burglary.

Once in federal court, they face stiffer sentencing guidelines than if they were tried in state court, where non-Native cases are generally heard. Diversion, probation and other mitigation, typical of state courts, are less common, as is a jury whose members include their peers, which is to say, other Natives.

As a result, Native Americans receive significantly longer sentences than non-Natives for similar crimes. The U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics says they are 38% more likely to be behind bars than anyone else. Native detainees are also, on average, younger, more likely to be women and more likely to have less criminal history than the federal prison population at large.

“For Natives accused of crimes, these are not simply injustices,” says attorney Brett Lee Shelton, who is from the Oglala Sioux Tribe. “They arise from essential components of the law itself.” Shelton is responsible for the Indigenous Peacemaking Initiative, which supports heritage Native justice, a program of the Native American Rights Fund, a nonprofit law firm.

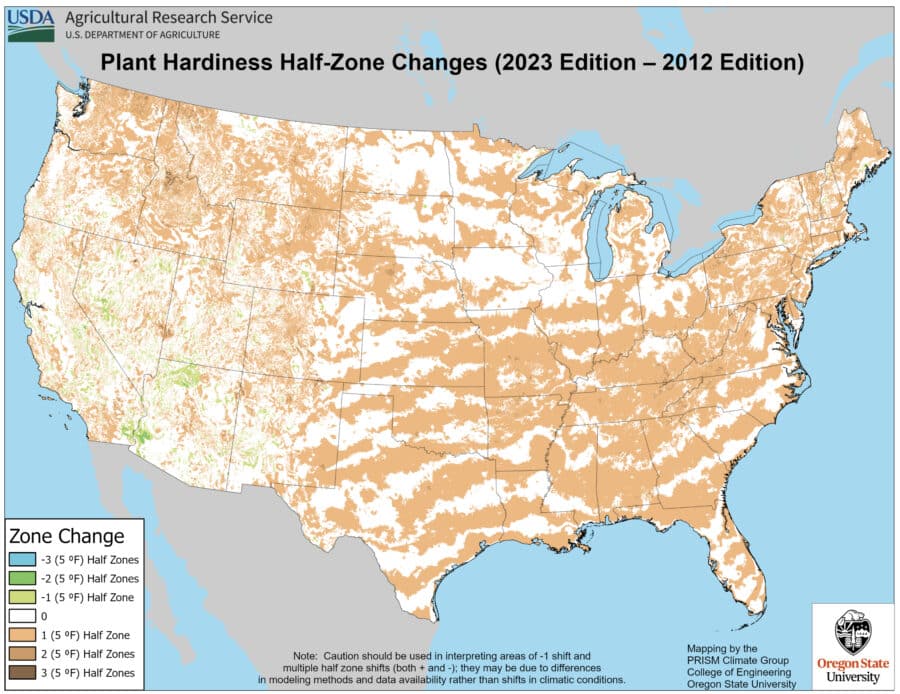

More than two decades ago, the U.S. Sentencing Commission—the agency within the Department of Justice (DOJ) that defines federal sentencing policies and practices—first met to address disparities affecting the Native population. The differences are spelled out in laws and Supreme Court decisions dating back more than 100 years, says Shelton. The phenomenon arose as the U.S. looked for cheaper ways than war to separate Indigenous people from their land and resources. According to Carl Schurz, a Union Army general who became Interior Department secretary in 1877, the U.S. was spending an average of $1 million per death—an enormous sum at the time—in fielding an army to battle Native people.

Officials of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), the Interior Department and other federal agencies began case-shopping, according to Sidney L. Harring, law professor at the City University of New York. They looked for an adjudication that would let the federal government control tribal justice. The Congressional Record shows in 1883 that Congress allocated just $1,000 to take to the Supreme Court a Rosebud Sioux case that had gotten underway two years earlier. For this cut-rate price, the confinement and execution of Natives was soon established in federal law—in particular, by the Major Crimes Act of 1885.

Still on the books, the Major Crimes Act establishes federal jurisdiction over a swath of on-reservation allegations—if the defendant is Native. This results in many crimes occurring on reservations being tried in federal court, effectively ensuring greater sentences for Natives than non-Natives. The Sentencing Commission found, for example, that on average an assault conviction in a South Dakota state court received a 29-month sentence but got 39 months in federal court. The spread in New Mexico was wider: six months versus 54. Similarly, a South Dakota state-court sentence for a sexual abuse conviction could be 81 months, as opposed to 96 in federal court. New Mexico’s range was again wider: 25 versus 86.

“I find it gut-wrenching when I am asked by a family member of a [Native] person I have sentenced why Indians [receive] longer sentences than white people who commit the same crimes in the same location,” says Ralph R. Erickson, chief District Court judge in North Dakota and a leader of the Sentencing Commission. But, he wrote in a report, “differences between state and federal sentencing law mandate the difference.”

“The system,” a Sentencing Commission report concluded, “is broken and needs change.”

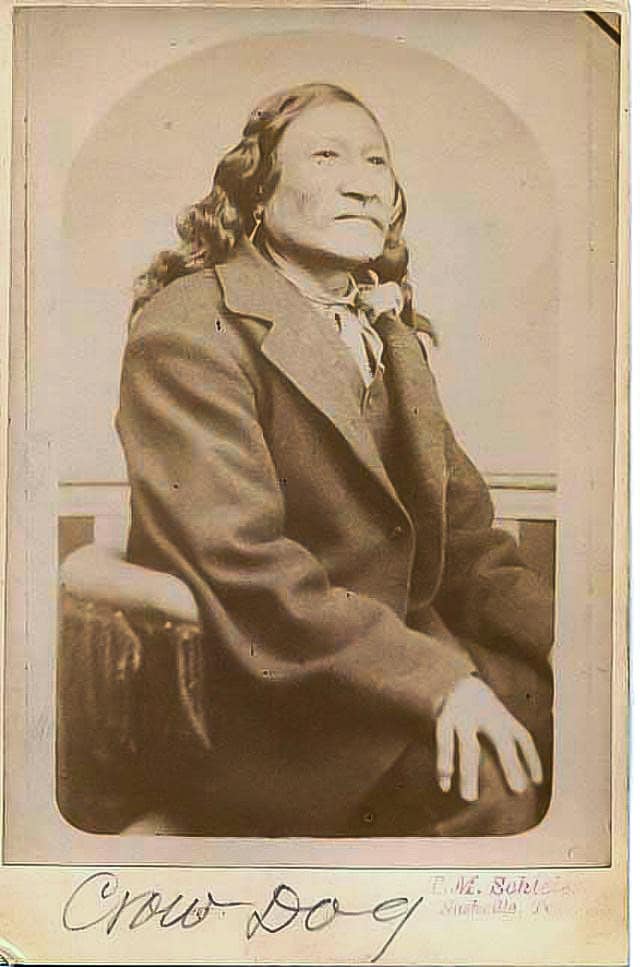

Crow Dog and the Major Crimes Act

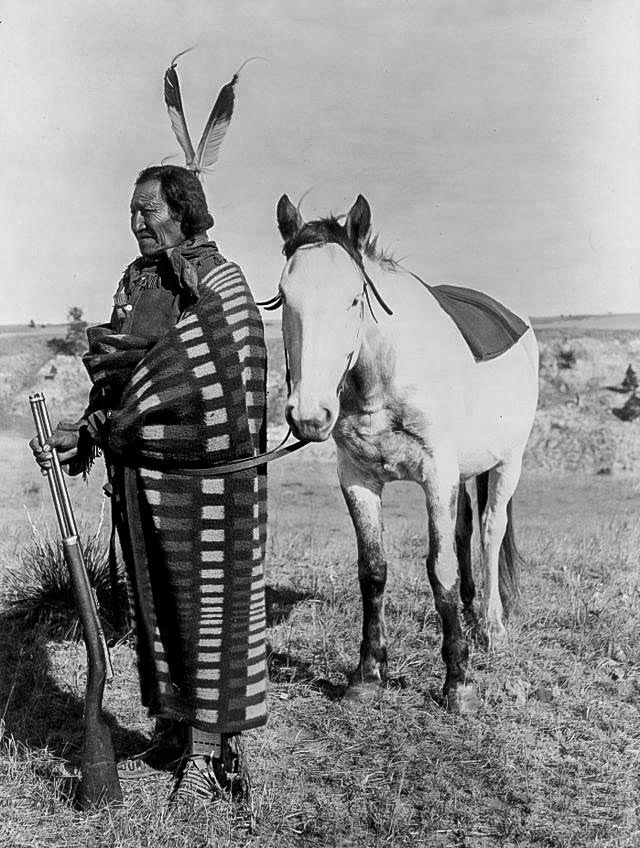

On August 5, 1881, gunfire rang out on the Rosebud Sioux Indian Reservation, in the Dakota Territory. Kangi Sunka, or Crow Dog, shot dead rival tribal leader Sinte Gleska, or Spotted Tail, as the latter was leaving a tribal council meeting. Local newspapers covered the story in detail from the initial incident through the final Supreme Court decision two years later.

After the shooting, the tribe directed Crow Dog to re-establish community harmony by giving Spotted Tail’s family horses, money and a blanket. When federal officials heard of the incident, they sent someone to arrest Crow Dog. He declined and instead went to a nearby Army fort, accompanied by a Rosebud chief, and turned himself in.

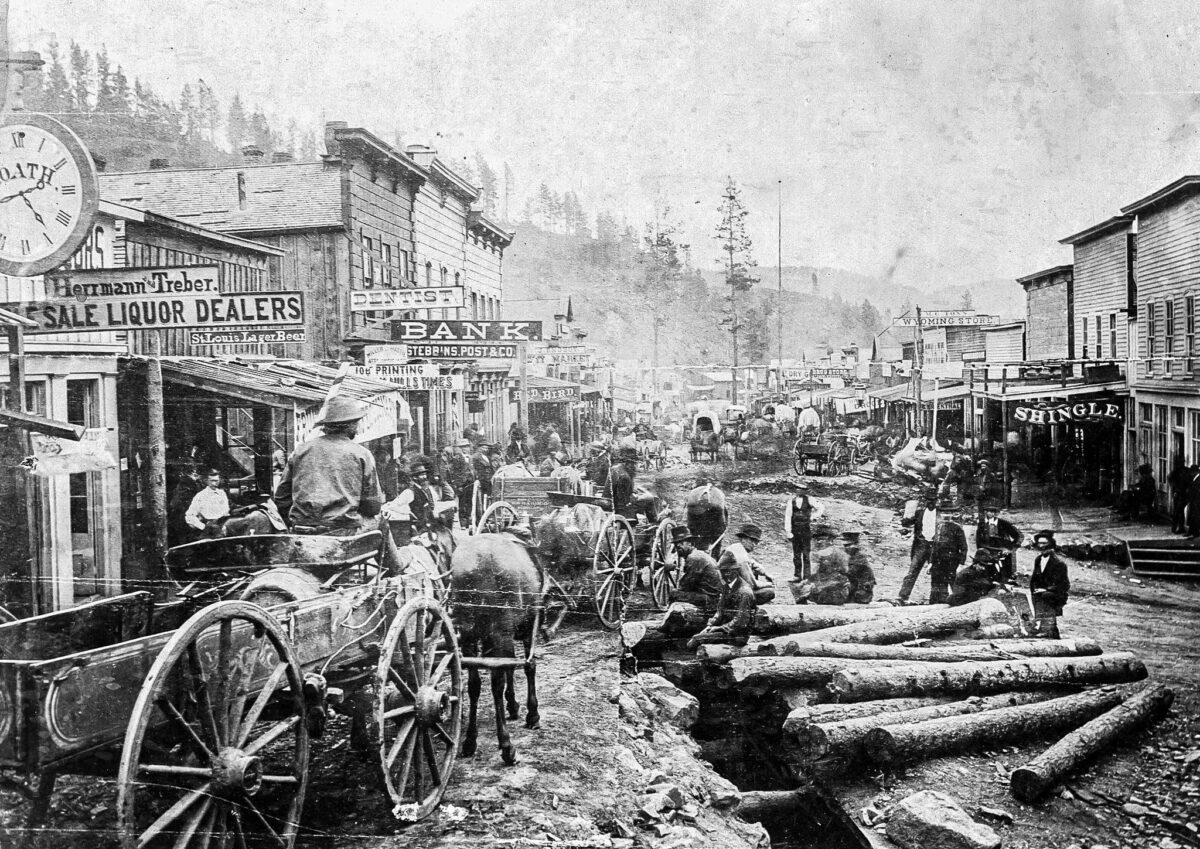

Crow Dog was later arraigned in Dakota Territorial Court in the town of Deadwood. Prosecutors there alleged that he had set up an ambush for Spotted Tail and planned to shoot him from the cover of his wagon. For his part, Crow Dog testified in court that he was behind his wagon because he was fixing its undercarriage, which had just broken. Spotted Tail apparently thought Crow Dog was lying in wait, pulled out his pistol and aimed it at him. Crow Dog saw this, he testified, grabbed his rifle and shot Spotted Tail.

Throughout the encounter, Crow Dog’s wife and baby were on the wagon’s seat—which begged the question: Who brings their family to a gunfight … and leaves them in the most exposed position?

Crow Dog’s lawyer, A.J. Plowman, worked most of the case in return for a few ponies. Plowman filed a plea of self-defense and challenged the Territorial Court’s jurisdiction over on-reservation offenses committed by tribal members. How the trial ended and the ensuing political maneuvers reverberate to this day.

As Crow Dog’s trial progressed, many attending it came to believe he had not set out to kill Spotted Tail. Instead, they told newspaper reporters, they thought the two men had defended themselves simultaneously in a confusing and fast-moving incident. Crow Dog was simply faster with his firearm. The attendees felt he would be acquitted or, at worst, found guilty of manslaughter.

Instead, Crow Dog was convicted of murder and sentenced to hang.

Though 19th-century Deadwood was a tiny frontier town on the western edge of what is now South Dakota, it was well acquainted with celebrities and celebrity trials. Calamity Jane, Wild Bill Hickock and other notorious gunfighters lived, loved and shot each other there. In 1876, a drifter named Jack McCall was tried in Deadwood for killing Wild Bill in a poker game. The cards Wild Bill was holding—pairs of aces and eights—came to be known as Dead Man’s Hand. Five years later, local newspapers were ready—and eager—for Crow Dog’s trial.

About a month after the shooting, the Black Hills Weekly Pioneer reported “at least one hundred pairs of eyes” had gathered to watch Crow Dog arrive at the Deadwood jail. Weeks of thrilling “fake news” in the Weekly Pioneer and Black Hills Daily Times had postulated just how the killing could have, must have, happened. The papers gave the tribal leaders disparaging nicknames: “the Old Dog” and “Old Spot.” Onlookers and the media were expecting a fearsome scoundrel.

Then Crow Dog appeared. He was quickly re-labeled “the distinguished Sioux,” described as handsome with a pleasant smile and lauded as brave, reliable and honest. His good looks should impress the jury, confided the Black Hills Daily Times. The Deadwood lockup seems to have tried to make its latest celebrity inmate comfortable. Crow Dog enjoyed ample meals “well cooked and cleanly served” and could invite guests to dinner, according to one paper. He whiled away his time making sketchbooks, which he gave away as gifts, and issuing weather predictions—much-admired in a part of the country with dramatic and quickly changing weather.

In a prequel to today’s red carpet coverage, the newspapers’ readers learned that one day Crow Dog wore to court a Native-style shirt and leggings with a matching blanket. On another day, he sported an outfit that would look fashionable today—dark blue sports jacket over dark blue shirt and trousers, no tie.

The papers carefully recounted the testimony, attorneys’ objections and judge’s rulings, along with racist comments from jury members. One jurist declared the testimony of one white man worth more than that of “one hundred Indians.” Another said he had “been pretty badly scared by them.”

When the sentence was announced, a reporter hit the streets. He learned that some courtroom attendees were pleased that Crow Dog would pay for the shooting with his life. Others hoped the case would confirm federal jurisdiction in the Dakota Territory and hasten its transition to statehood. Most were shocked by what they saw as double jeopardy, or being tried twice for the same crime. They knew this was forbidden by the Constitution’s Fifth Amendment and that the tribe had already resolved the tragedy according to its own laws. How could Crow Dog be tried again? The newspapers published articles puzzling out this question from varied points of view.

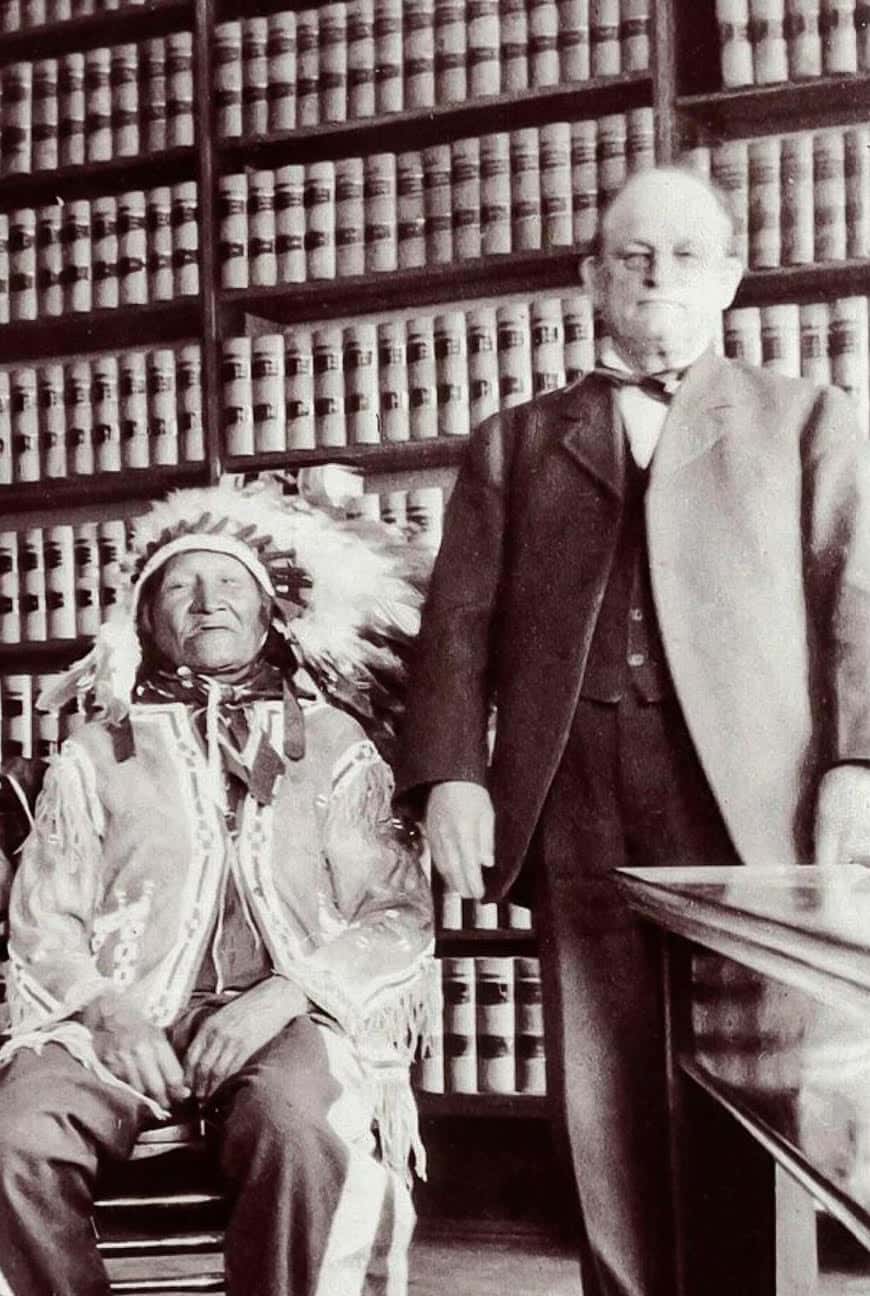

After Crow Dog was convicted, his lawyer filed an appeal, which made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1883, the Court vacated the conviction, ruling that tribes retained the right, as an attribute of their sovereignty, to be governed by their own laws on their own reservations.

When Crow Dog was released from the Deadwood jail, he walked through town, shaking hands with his many well-wishers and accepting gifts: winter boots, woolen socks, a heavy coat and more. He dined with Plowman and his wife.

None of them saw the trap. The case-shopping Washington officials had studied a few trials and their outcomes. They felt Crow Dog’s was most likely to spur Congress to act: Spotted Tail was a prominent tribal leader who had supported negotiation with the federal government on important matters, and his death could be sold as a loss to the United States. Deadwood had little communication with the East Coast in those days, and the Washington officials felt free to claim there had been a “public outcry” when the Supreme Court freed Crow Dog. The claims were false, writes law professor Harring, who did extensive research and found no evidence of this.

Nevertheless, federal officials began lobbying Congress for more power over tribal nations. They described the tribes as lawless and ruled by “blood revenge,” according to Chickasaw tribal citizen Kevin Washburn, dean of the University of Iowa College of Law and former Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs. They claimed federal legal oversight would provide tribes with increased public safety. “Though this justification was based on false and misleading information, it has proven the most durable,” Washburn writes in the North Carolina Law Review.

Two years later, in 1885, the Major Crimes Act became law. It let the federal government reach into tribal nations and control their judicial systems, thereby destabilizing communities and degrading public safety. The list of crimes covered has lengthened through the years, and Supreme Court has bolstered the law with decisions declaring that Natives have no jurisdiction over non-Natives.

At about this time, the federal government was defining reservations in a way that undermined the tribes even more, says Cherokee attorney Scott Sypolt, who practices federal Indian law, the portion of U.S. law pertaining to the tribal nations. The set up was comparable to a concentration camp, Sypolt says; if tribal members left without permission in the early days, the Army drove them back and shot those who resisted. Dividing the reservations into individually owned plots further weakened the tribes by destroying age-old land use patterns typically based on cooperative work and shared results.

Chaos Theory

Laws regarding Indian Country justice have accumulated over time such that which entity is in charge of a case (the federal government, a state or a tribe) depends on the Native or non-Native status of the alleged offender and victim, the type of offense and where it occurred, among other factors. Harring equates the aggressive attempts to control tribal members that followed the Crow Dog decision to “the Dred Scott case and the internment of U.S. citizens of Japanese descent in concentration camps.”

Attorney Charles Abourezk, now chief judge of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe Supreme Court, in South Dakota, was part of a legal team that successfully defended tribal council members of nearby Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. In the early 2000s, U.S. authorities charged the council members with “felony failure to pay rent” and had them arrested publicly at their offices, rather than at their homes, dragging them out in ankle chains, Abourezk recalls. If convicted, each faced as many as 25 years in prison.

The federal government claimed that the council members should have based rental charges for on-reservation properties on the renter’s income—not on the property’s market value. According to the U.S. government, this meant that they were in arrears, a legal term for payments or debts that are overdue, for properties they personally were renting and should be imprisoned. After years of drama, a judge dismissed the charges, noting that the United States abolished debtors’ prisons long ago. The U.S. Attorney’s Office in South Dakota brought the case, but declined to comment on it.

To non-Natives, the melodrama of the charges, the arrests and the threatened sentences may sound preposterous. They’re not, says Joseph Holley, chairman of the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone Indians in Elko, Nevada. That’s because a tribe’s reservation is held in trust by the federal government, Holley explains, and something seemingly innocuous can be magnified into a federal offense. Abourezk says this possibility is about striking fear into tribal members.

Many see the case of leading Native activist Leonard Peltier as a debacle of the U.S. justice system. With fabricated evidence and shifting charges, he was convicted in 1977 of aiding and abetting murderers who had already been acquitted. Peltier, who is of Anishinaabe, Lakota and Dakota descent, was sent to federal prison, where he has remained for nearly half a century. Pope Francis, the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the Dalai Lama and other eminent leaders worldwide have called for Peltier’s release.

In 2021, retired U.S. Attorney James Reynolds, who prosecuted Peltier, wrote to President Joe Biden, saying he now realizes Peltier’s conviction was shaped by “the prevailing view of Native Americans at the time.” He urged Biden to grant Peltier clemency and “take a step towards healing a wound I had a part in making.”

Peltier’s clemency petition is again under review, according to DOJ’s Office of the Pardon Attorney. Peltier’s attorney, Kevin Sharp, of the firm Sanford Heisler Sharp, says he is “more hopeful than ever that something positive will happen.” Sharp credits his optimism to recent public outcries for clemency, along with publicity for the September 2023 gatherings outside the White House commemorating Peltier’s 79th birthday.

In a 2021 DOJ report entitled “Indian Country Investigations and Prosecutions,” U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland declared the department “committed to partnering with Tribal communities, governments, courts and law enforcement agencies to help reduce crime and support victims.” To this end, DOJ has given tribes grants, access to national information resources and much more.

However, the DOJ report also describes the impossibility of accurately documenting either the efforts or the results and determining their impact. The Sentencing Commission noted a similar problem: crafting solutions required data it didn’t have—especially from states with large Native populations. It was impossible “to complete a robust comparison of the sentences received or served by non-Indian and Indian defendants in federal and state courts,” according to the commission’s Tribal Issues Advisory Group.

The View from the Other Side

While the federal government vigorously pursues Natives alleged to have committed even minor crimes, it may ignore some serious ones, says William Main, of the Aaniiih. Main is a tribal court lay advocate and former chairman of the Fort Belknap Indian Community in Montana. The chance of the government’s neglect is especially likely, he says, “if it’s Native crime against another Native. In that case, it will often go unpunished.”

Says Holley, of the Western Shoshones: “There’s no definitive line about how [Native] people are going to be treated by the law.” The unpredictability destroys confidence in the justice system, says Western Shoshone Council member Tanya Reynolds, from the South Fork Reservation in Spring Creek, Nevada.

Wyn Hornbuckle, deputy director in DOJ’s Office of Public Affairs, wrote in an email that DOJ is determined to change this. The agency’s “efforts to enhance public safety and sovereignty of Native Americans … accelerated significantly after the passage of the Tribal Law and Order Act in 2010 and continue today.” That law has, among other things, increased the number of law-enforcement officers on tribal lands.

But, according to Main, there still aren’t enough federal agents in Indian Country. Tribes have taken the federal government to court over this. In 2023, the Oglala Sioux Tribe, on the 3.1-million-acre Pine Ridge Reservation, sued the BIA for inadequate policing. Some 30 officers and seven criminal investigators patrol 30,000 tribal members in an area nearly the size of Connecticut. The business committee of the Ute Tribe, on the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, in Utah, says that at most three BIA officers patrol its 4.5 million acres.

Luella Brien, the Apsáalooke founder and editor-in-chief of Four Points Media, covers news on the Crow Reservation in Montana. Brien knows of dangerous non-Native perpetrators—drug dealers, human traffickers, rapists and others—hiding out on reservations. Thanks to the limits on tribal jurisdiction, Brien says, “Non-Native criminals feel safer on the reservation.”

Main agrees, saying that non-Natives often complain to him that “reservations are havens for criminals.” He tells them, “Yes, but it’s not the Indians they’re a haven for.” Indeed, American Indians and Alaska Natives are more than twice as likely as non-Natives to be victims of violent crime, often at the hands of non-Natives, says the National Institute of Justice.

The Ute Tribe’s business committee says the federal government does not support its efforts to address related judicial issues. The tribe built a state-of-the-art detention center on its Utah reservation in order to safely house and rehabilitate as many as 100 prisoners adjudicated under federal and tribal law. In the years since the center was finished, the BIA has not hired enough staff to handle more than a few inmates at a time, and the tribe does not have the legal authority to hire the required federal employees. The BIA did not respond to multiple requests for a comment.

The Supreme Court upheld the limitations on tribal justice in the 2021 case United States v. Cooley. The lawsuit was based on events of a cold February night in Montana. A tribal police officer came upon a truck stopped on the shoulder of a lonely Crow reservation highway. The officer wondered if the vehicle’s occupants needed assistance. What he found was a non-Native driver with red eyes, slurred speech, bags of meth, wads of cash, loaded guns and a toddler.

The officer contacted state and federal officials, and the driver was eventually charged in federal court with drug trafficking. His lawyers convinced lower courts that the tribal officer had exceeded his authority. The Supreme Court disagreed, saying the tribal officer could apprehend the driver as long as he handed him over for investigation and prosecution—which he had done.

In sum, the federal government doesn’t protect tribal communities, and the tribes aren’t allowed to, according to attorney Shelton. “Undoing the Major Crimes Act and related laws and court decisions is essential,” he says. However, Shelton believes that getting the federal government to reverse course will be difficult. For decades, it has supported tribal self-determination in education, healthcare, environmental regulations and other areas—but not criminal law. Bringing tribes back into the picture and determining the resources they need to proceed would be a time-consuming community-by-community effort, says Shelton.

Circles of Traditional Justice

The way the Rosebud Sioux Nation handled Spotted Tail’s death—before the U.S. government got involved—is an example of time-honored Indigenous justice. Called peacemaking or restorative justice, it prioritizes healing, Shelton says. Once emblematic of Native communities worldwide, many—in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and beyond—are reviving it.

“We tend not to throw people away—to throw them into prison,” Shelton says. He adds that Indigenous cultures believe a misdeed arises from imbalance, which can be corrected through actions like restitution, apologies and community service. “We ask what we can all do together to help each of the people involved.”

The goal is healing perpetrator, victim and community. The success of this approach is apparent when comparing recidivism rates of two groups—recipients of federal sentencing and participants in Indigenous peacemaking. The Federal Bureau of Prisons finds that 45% of released prisoners are back in custody within a few years. In contrast, Shelton says, compliance rates for peacemaking participants are in the 90% range.

Laurie Vilas is a peacemaker with the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe in Minnesota. A citizen of the White Earth Nation, also in Minnesota, Vilas describes welcoming those involved in a case to sit in a circle. This arrangement is based on Native talking circles, in which each participant talks in turn, uninterrupted, and the group then seeks consensus. She encourages crafting the decision-making with universally held Indigenous values—love, respect, courage, honesty, humility, wisdom and truth.

Vilas recalls another community that used circles to welcome home returning prisoners. “We didn’t call them felons. We called them returning citizens,” she says. They got practical help, such as advise on résumé writing and job interviews, as well as cultural support. “We gave them a shell, sage, sweetgrass and tobacco—the four medicines—to honor them for going through tough times.”

According to Vilas, emphasizing culture reduces recidivism by letting a person know who they are and what they’re capable of. A 2023 MacArthur Foundation report describes similar methodologies used by tribal nations around the country.

By holding onto heritage values, Indigenous communities have endured unimaginable depredations, according to attorney Sypolt. “Massacres, germ warfare, sterilization, forced separation of children from parents, each and every element of genocide,” he reckons.

“They’ve tried in every way, shape and form to get rid of Natives,” says Reynolds, of South Fork. “They have not succeeded.”

The author thanks the Native American Rights Fund and Indigenous Peacemaking Institute for source material used to report this story. In These Times published another version of this article in March 2024.

Have thoughts or reactions to this or any other piece that you’d like to share? Send us a note with the Letter to the Editor form.

Want to republish this story? Check out our guide.

More from Barn Raiser

Finger Lakes Residents Fight to Enforce Constitutional Right to a Clean Environment