Sister Kerry Handal has spent many a cold winter’s day on the brisk shores of the Shinnecock Bay, working a kelp farm owned by the Shinnecock Kelp Farmers, a collective of six women who are enrolled members of the Shinnecock Indian Nation. The 63-year-old Handal, a sister of the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph (CSJ), might be found checking the lights in the kelp hatchery, saying a kind word or two to the tiny seedlings growing in fish tanks, or out in the bay wrestling kelp lines in her bulky rubber overalls and waders.

Shinnecock Farmers and Nuns Use Kelp To Restore Bay Ecosystem

Members of the Long Island-based tribe and local Sisters of St. Joseph have a long history of supportive partnership

Handal loves these waters. They are spiritual to her, they’ve been home for 40 years, and now, they’re in crisis.

Shinnecock Bay is tucked into the south fork of Long Island where overdevelopment, lack of municipal sewer systems and fertilizer leakage have created dangerously high levels of nitrogen. This problem grew worse when New York City residents began fleeing the pandemic for the Shinnecock Hills, “stress[ing] the already lacking infrastructure,” explains Shinnecock kelp farmer and tribal attorney Tela Troge.

This nitrogen and associated algal blooms, alongside overfishing and habitat destruction, have killed off much of the bay’s marine life, life that the maritime Shinnecock Nation Tribe had always depended on for food. In need of a new means of sustaining themselves, the Shinnecock have turned to kelp.

Help from kelp

One of the oldest self-governing tribes in New York state, the federally recognized Shinnecock Indian Nation has historically owned and occupied its aboriginal homelands in and around the Town of Southampton for the last 12,500 years. They were once part of a larger group that inhabited all of Long Island. As colonization progressed, the Shinnecock people were pushed out of their homelands into the modest 800-acre reservation where half of the 1,600 tribe members now reside.

This reservation is on a peninsula that is particularly vulnerable to the threat of intense Atlantic storms and rising sea levels. Its flood risk in the next 30 years is considered “extreme” by the climate modeling site Risk Factor. This has given the Shinnecock a new sense of urgency to protect their land.

In 2019, PBS aired a documentary, Conscience Point, that highlights the centuries-long struggles of the Shinnecock to maintain their traditions and land as one of America’s wealthiest communities built up around them. In the film, one of the Shinnecock women, Becky Genia, speaks about how the Shinnecock have traditionally harvested and used seaweed for medicine, beauty products, food, fertilizer and insulation for housing.

The movie was seen by Toby Bloch, the director of infrastructure for GreenWave, a global nonprofit supporting “regenerative ocean crops to yield meaningful economic and climate impacts.” Bloch reached out to Genia, proposing they work together on a kelp farm. Genia was interested, but she knew they would need better access to the bay, and she thought she knew some people who might help.

In January 2021, Genia emailed Sr. Joan Gallagher, the chair of the CSJ’s Earth Matters Committee, explaining her vision for starting a kelp farm to restore the waters. But to do so, they would need access to the waters from the sisters’ retreat villa. Gallagher was sold.

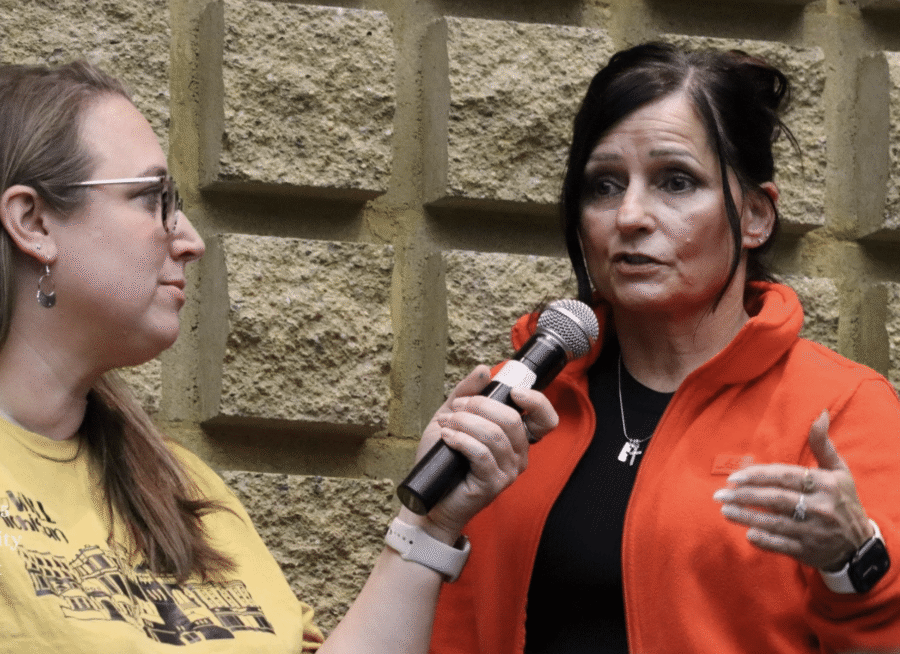

“I thought it was great,” explains Gallagher. The CSJ is known for its environmental social justice work, and she brought the request to the council of sisters. “I said, ‘How can we deny them this? The bay has their name!’ ”

Within a few months they were off and running. The sisters converted one of the cottages on the property into a hatchery where they could grow seedlings in a controlled environment under lights. Out went the dated furniture and religious books, and in came the fish tanks, fluorescent lighting and nursery spools. The Shinnecock Kelp Farm was open.

Growing sugar kelp helps absorb nitrogen, combatting ocean acidification by sequestering carbon and extracting nitrates from the water. Sugar kelp also makes an excellent fertilizer, popular among farmers, which the sisters plan to sell.

In the fall, the Shinnecock farmers collect fertile sections of kelp to get the spores settled around twine in their hatchery where they will grow over the next six to eight weeks in tanks with added fertilizer. The farmers then outplant them on spools tied to buoys where they will grow until harvest season, which starts in April. Harvested kelp can then be processed into fertilizer and sold to farmers, golf courses and other buyers, or else used for pharmaceuticals, beauty products or food. For the Shinnecock reservation residents, many of whom live in poverty, kelp farming could be a lifeline. All profits from fertilizer sales will go to the Shinnecock Nation. When the Shinnecock broached how to share the profits, Gallagher made it clear: “This is your project. …. We’re not looking for a cut.”

Growing trust

The relationship between nuns and Shinnecock had begun years before. In 2019, Tela Troge recounts, New York University Dental School returned the remains of Shinnecock children they had been using for study to the Shinnecock Nation for burial.

“We like to rebury them as close as possible to where the remains were taken from,” Troge says. This brought them to the Sisters of St. Joseph’s mother campus in Brentwood, N.Y.

“I drove to Brentwood. I had never met them, we didn’t have a relationship with them,” remembers Troge. “But the sisters were just so welcoming.”

“They came into the land we have in Brentwood and they wanted to see what place was calling them,” Gallagher remembers. “They found the place in our own cemetery, our own grove of our own ancestors.”

The Shinnecock invited the sisters to partake in the burial ritual, offering explanations and translations to the dozen sisters gathered. Afterward, they all shared a meal of corn, beans and squash and quickly realized they were kindred spirits. “It really amazed me how closely our values aligned,” Troge says. “We have the same regard for the land, water and stewardship.”

Gallagher says, “When you have a conversation and you listen to the Shinnecock people, to their spirituality, and their sense of knowing, their deep knowing that all is one under the creator within this universe, I remember thinking, ‘I don’t know if you’re Sisters of St. Joseph or we’re Shinnecock.’ Our spirits were very much in alignment.”

The sisters will find a way

This foundational moment set a precedent for years of allyship, in which the nuns became some of the Shinnecock’s biggest supporters. When the Shinnecock were sued by the state of New York for constructing billboards advertising Shinnecock products without a permit, the sisters joined in on a fierce advocacy and letter-writing campaign. When the sisters heard Troge was unable to breastfeed her son, the next week a pallet of baby formula arrived at Troge’s door.

When the kelp farm was starting during the pandemic, the sisters would Zoom call the kelp, singing songs, offering kind words and reading poems, something the kelp farmers and sisters say made the growth of their seedlings mushroom. When one of the older kelp farmers was struggling to get to the kelp farm each day, the sisters sent her a vehicle. This winter, one of the homeless elders will be living with the sisters.

“Literally anything, big or small, the sisters will find a way,” Troge says. “I don’t think we’ve ever experienced a relationship like this. Our voices for so long had just been erased or silenced or there was no help for us. … They’re willing to use their voices to advocate for us, and leverage the political power they hold.”

“We’re standing with these people because it’s right,” Gallagher says. “And it’s their land.”

Moving together

In the two years since the kelp farm started, the Shinnecock and sisters have seen an increase in shorebirds they hadn’t seen in the area before, in scallops and horseshoe crabs, seahorses and sharks.

“What’s blown me away is the absolutely incredible increase in biodiversity,” Troge says. “It’s a directly observable sign that what we’re doing is working.” In the fall of 2022, they expanded their hatchery ten times to 200 spools of kelp and to three different farm sites. “Our plan is to extend to open ocean farming with farm sites over one square mile,” Troge says. “We already brought on four new Shinnecock crew members on staff.”

A Shinnecock word was used in a meeting with the sisters last year that has stuck with Gallagher ever since—mamaweenenee. It means, “we move together.”

“I think that that says it in a line, a desire to want to move together. Because we know in our heart of hearts that it’s just one sacred community,” Gallagher says. She feels anger and “a deep sadness that people who have lived as one with the land since the last ice age have not been treated with dignity and respect. They have not been recognized or listened to. If we had listened, the bay and other waters would be teeming with life and sustenance.”

But Gallagher, Handal and Troge are looking with hope, as the Shinnecock do, seven generations ahead. “If we continue to live out of this gift of active inclusive love, then there will always be a movement toward oneness,” Gallagher says. “I believe that makes the creator very happy.”

Casey McCorry is a freelance writer and documentary filmmaker based in Detroit, Michigan.

Have thoughts or reactions to this or any other piece that you’d like to share? Send us a note with the Letter to the Editor form.

Want to republish this story? Check out our guide.

More from Barn Raiser

Big Ag Has Corrupted Our Food System. Here’s How We Can Rebuild.

Data Centers Are Reshaping Local Politics in the Great Lakes