In April 2023, a small town newspaper in rural Oklahoma published a story about a local sheriff and members of the county board of commissioners who had been recorded making wishful comments about lynching Black people and killing the newspaper’s publisher and son who ran the paper together and had angered the officials with critical coverage.

How Oklahoma State University Plans to Boost Rural Journalism

Local news faces major challenges. Small town journalism internships offer a promising solution.

The story, published in the McCurtain Gazette in McCurtain Countydrew global attention to the county of 31,000 people at Oklahoma’s southeastern border. The story reverberated throughout the nation, with Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt calling for the state attorney general to investigate the sheriff and for the county officials to resign.

It also put a spotlight on the importance of local, rural journalism.

“We’ve seen in McCurtain County, it can be dangerous to report what’s happening,” says Rosemary Avance, an assistant professor at the School of Media & Strategic Communications at Oklahoma State University who has studied local news habits of Oklahoma residents.

At a time when rural news and media outlets across the country face under-staffing, significant financial stress and threat of closure, local journalism advocates say it’s more important than ever to recruit and train reporters to work in rural and small towns. That’s why Oklahoma State University recently launched a Rural Journalism Internship Fund to create a rural journalism internship. The internship seeks to help fill a void in areas lacking trained journalists.

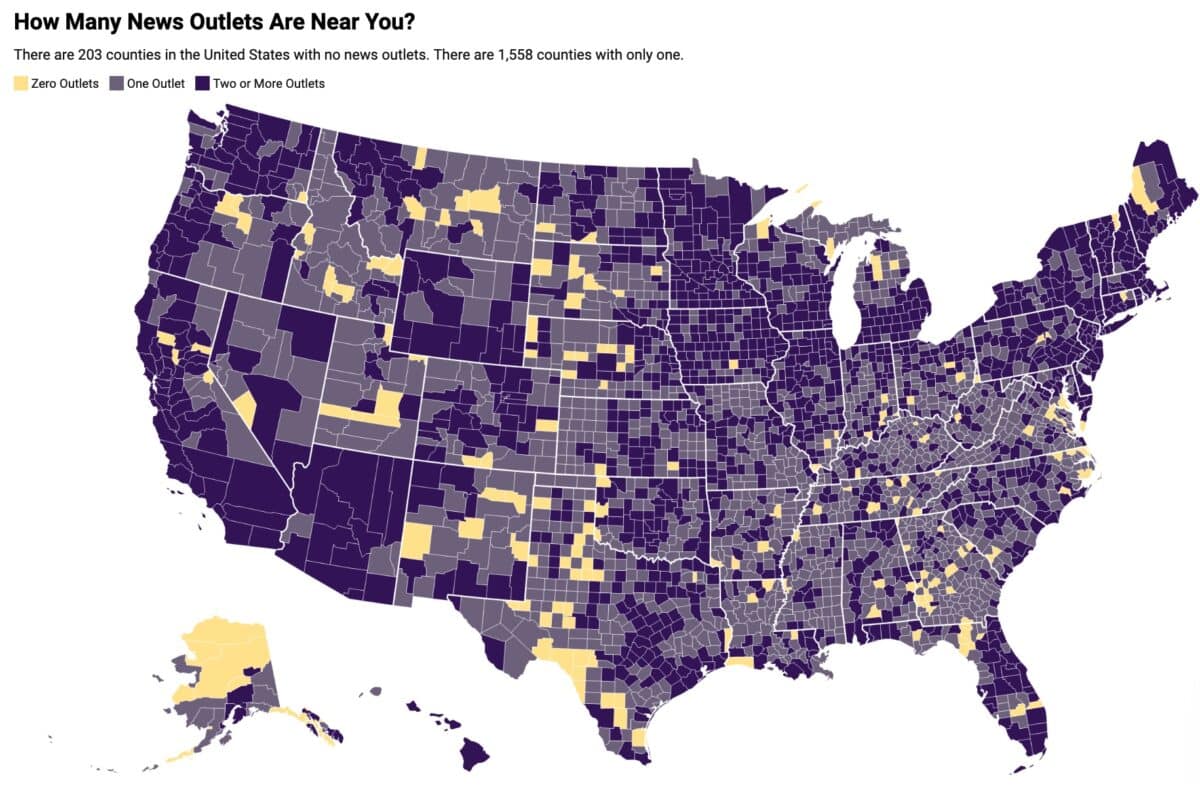

“There’s a large phenomenon already known as news deserts, where there’s areas where news coverage is really poor,” says Jared Johnson, director for OSU’s School of Media & Strategic Communications. “We came up with an idea that we could set up a grant fund to help fund students that might want to have a journalism internship experience in a rural community.”

Johnson says working with small town newspapers is a win-win for the community and for students. The community and local media outlets (the internship fund supports students in a variety of print, audio or visual media) get more support to report the news, while the students are able to tackle many different topics and cover a variety of stories, especially stories they might not be able to cover at a larger daily paper.

“Most of these newspapers, radio stations, maybe even some smaller TV stations, they’re underfunded,” Johnson says. “They’re understaffed. They don’t have a lot of people to do the work that needs to be done to bring news to the local community.”

Student journalists, meanwhile, have the training and know-how to cover city council and other government meetings. “They understand making connections with people in the community and building sources,” Johnson says. “They understand the needs that the community might have, and how to tell a story, and how to do it in a fair, balanced, non-partial way so that people in the community can get that sort of information and know what’s going on.”

The internship was crowdfunded and raised more than $5,600 with the first $5,000 matched.

Associate Professor Joey Senat is working to get students interested in the rural journalism internship.

“For the rural outlets, it’s not only for them, but it’s for their audiences,” he says. “They need help. They need more people. The entire news industry is being squeezed right now by the economics.”

There are slightly more than 204 counties that are considered news deserts, with no newspapers, local digital sites, public radio newsrooms or ethnic publications, according to Northwestern University’s Medill School’s State of Local News 2023. The report identifies another 228 counties at serious risk of becoming news deserts in the coming years.

According to Senat, if they can provide one more person to do quality journalism during at least a few months, he believes the school has an obligation to do that. “News organizations need an extra set of hands and eyes on local government,” Senat says. “And that’s what their audiences need. The audiences need watch dogs in their areas.”

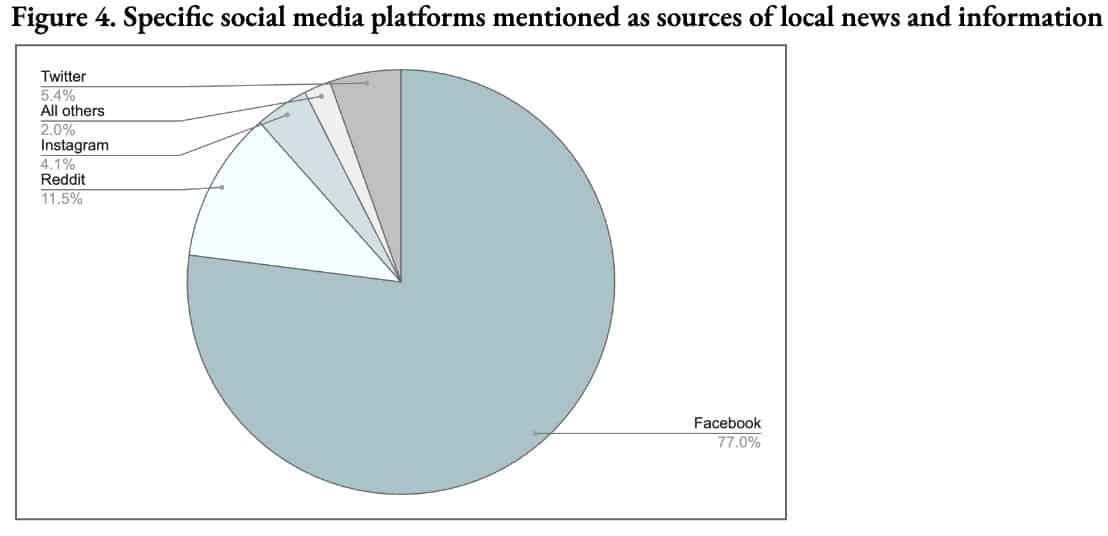

Senat describes a local resident who covers Guthrie, Oklahoma, where Senat lives, and posts the material to the Guthrie News Page on Facebook. “He’s going out and he covers the county commission meeting” he says. “No one else is doing that. He also broadcasts it live. So those places exist.”

The study of Oklahomans’ new habits Avance worked on was conducted with Allyson Shortle, associate professor of political science and co-founder of the University of Oklahoma’s Community Engagement and Experiments Lab. It’s the first qualitative observational study of both news deserts and underserved metro communities statewide in Oklahoma.

The study found that most residents rely on social media and community word of mouth for local news. In addition, small town residents express more trust in local news when a local person is in charge of providing it.

But they don’t want to pay for the news, according to Avance. Few study participants were interested in paying for news, let alone local sources. “Broadly, we found that people don’t want to pay for news,” she says. “They believe it’s important. They think they should have it. They don’t want to pay for it, and they don’t want advertising to support it either. So that’s a problem.”

The study also found that people think the government should subsidize news outlets, yet, at the same time, they don’t want to pay additional taxes to fund such a public service.

“But they do think that news access should be a public good,” she says. As a result, education about the news is a critical component of building public understanding. “I think there’s a little bit of a lack of understanding of the reason why news is independent and not government sponsored.”

Still, Avance thinks it’s important for students to intern at rural and small town newspapers. “If we can get our students to go intern in areas where the internship can serve a social function as well, and do some social good, then I think that that’s worth getting our students out there and motivating them to look for those jobs.”

Kristi Eaton is a freelance journalist in Oklahoma, formerly with the AP in Oklahoma and South Dakota. She covers social justice issues, gender, travel and more, with a focus on solutions-based stories. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Associated Press, The Washington Post and elsewhere. Visit her website at KristiEaton.com or follow her on Instagram @KE_Comms.

Have thoughts or reactions to this or any other piece that you’d like to share? Send us a note with the Letter to the Editor form.

Want to republish this story? Check out our guide.

More from Barn Raiser

The Candidate From Rural Maine Fighting Big Money

The Grassroots Organizing Revival in Rural Washington