This is the second installment of Barn Raiser’s 2024 election coverage series “Charting a Path of Rural Progress,” which features interviews with rural policy experts and organizers who came together in Omaha, Nebraska, in 2023 to forge a rural policy platform on which candidates can run—and to which voters can hold their elected leaders accountable. The platform that grew out of that Omaha meeting, A Roadmap for Rural Progress: 2023 Rural Policy Action Report, released last October, details 27 legislative priorities for rural and small town America, based on legislation that has already been introduced in Congress.

Organizing State Legislators to Think Rural

‘Rural people need policymakers working at all levels on their behalf’

Kendra Kimbirauskas is the Senior Director of Agriculture and Food Systems at the State Innovation Exchange (SiX), a national nonprofit that organizes with state legislators to enact progressive legislation. More than 3,500 state legislators across all 50 states are in its network. Each year SiX publishes the annual Blueprint for Rural Policy Action in the States, which is the state-based addendum to the Rural Policy Action Report.

Kimbirauskas, 45, a first generation American, grew up in Ingham County, Michigan, the daughter of a dairy farmer who was a World War II refugee from Lithuania. She studied German and International Relations at Michigan State University in East Lansing. Currently she farms with her husband, Ivan Muluski, on 70 acres near Scio, a town of 961 in Linn County, Oregon. They raise Jersey X Wagyu beef cattle and have two dairy cows, which Kimbirauskus milks for personal use.

What’s your background?

I am a child of the 1980s farm crisis. When the price of milk went through the floor, my parents were forced with the choice of either selling our dairy herd or losing the farm. That was a really tumultuous time. Not only did my family have a really hard time—they lost their livelihood and had to get into a different business—but I saw a lot of our neighbors suffer as well. I saw our rural community deteriorate after many dairy farms went out of business and some farmers moved away. In real time, I saw our main streets and rural businesses disappear. And then, NAFTA came and took a lot of jobs away as well. I saw the destruction of not only rural areas, but rural economies.

Those early days were very formative for me. I get very frustrated with some in the progressive movement who discount rural people and the value that we bring.

How is the State Innovation Exchange (SiX) working in rural America?

I joined SiX in 2018 to develop the Agriculture & Food Systems program. The Ag program remains the bedrock of a lot of the work that we do, but our program has evolved to ensure that the legislators with rural districts have what they need to be strong champions for their constituents. We are working to ensure that all programming at SiX is what we call “rural inclusive,” and that the broader progressive movement doesn’t leave rural people behind.

We are using the Blueprint for Rural Policy Action in the States and the communications toolkits that go along with it as an organizing tool to work with state legislators so that they can engage rural issues more effectively. We have also established a rural working group for state legislators representing rural districts so they can work together across state lines and with partners on issues that their rural constituents face, while sharing ideas, strategies and lessons learned from their colleagues. As part of this work, we organize tours to rural communities for legislators to learn firsthand from rural people how corporate power and consolidation are driving the demise of the family farm economy, decimating rural communities and accelerating increased rural poverty.

What are the national priorities around food and agricultural issues that you see state legislatures tackling and addressing?

State governments are generally closer to the people and more accessible. There are a number of policy issues that states can work on to move the ball in the right direction for rural people. The state policymakers that we work with are eager to partner with community leaders and advocates toward advancing shared goals. When states take action to improve the lives of rural people, it presents a unique organizing opportunity to make the case for federal action.

In 2023, SiX released a complimentary document to the Rural Democracy Initiative’s Rural Policy Action Report called the Blueprint for Rural Policy Action in the States. It is a roadmap of very tangible policies that state-elected officials and local advocates can use and tailor to the needs in their states, even as they wait for Congress and the federal government to take action.

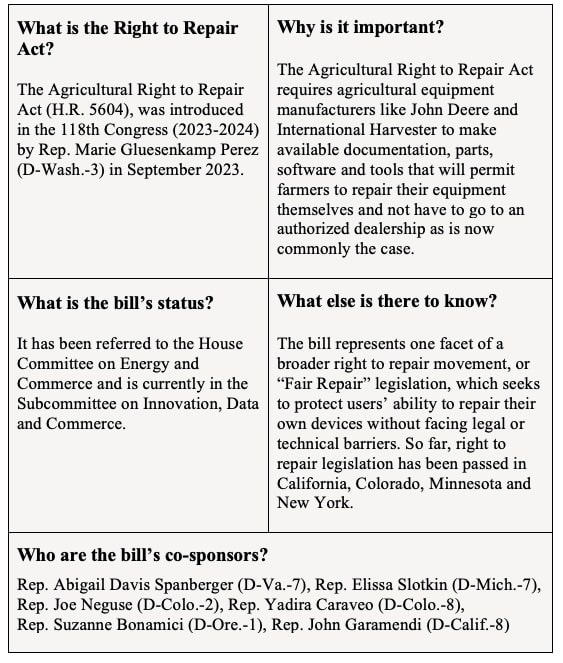

For example, while the federal government explores whether to enforce antitrust law, we’re hearing concerns about the concentration of wealth, corporate consolidation and corporate power. One way that states are pushing back is with legislation like “right to repair” laws. One of our members, Rep. Brianna Titone (D) passed a right to repair law in Colorado that allowed farmers to repair their own equipment and not be bound to only getting it repaired by the dealership where they purchased it. Other states like Michigan are also exploring “right to repair” laws as well. This past November, SiX hosted a meeting at a California ranch for legislators interested in agriculture and rural issues. There were 44 legislators from over 30 states and there was a lot of talk about “right to repair” laws and pushing back against agricultural monopolies. [In the U.S. House of Representatives, Rep. Marie Gluesenkamp Perez (D-Wash.-3) introduced The Agricultural Right to Repair Act in September 2023.]

Legislators working with SiX are also looking at the role regenerative practices can play in mitigating climate change while protecting communities from extreme weather events. When regenerative agriculture policy is done correctly, it can spur rural economic development through rebuilding local food economies while simultaneously creating opportunities for community food sovereignty and independence, which as the Covid-19 pandemic demonstrated, is critical during a crisis.

But we also need the federal government to step in and not only invest in these communities, but also pass legislation that can support rural communities across the board.

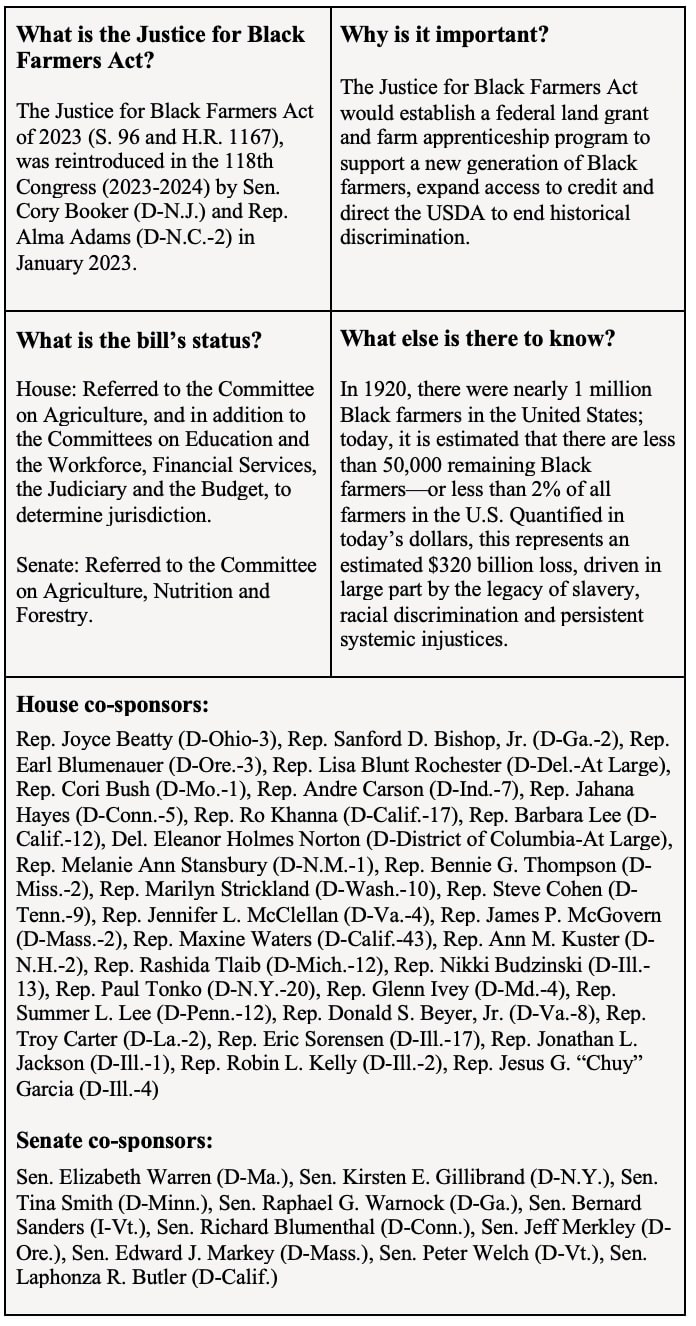

Inspired by New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker’s Justice for Black Farmers Act, state legislators in Illinois, Ohio, California, North Carolina and South Carolina have introduced state versions of the bill. It has been wonderful to see state legislators partner and build relationships with farmers of color to craft legislation that seeks to overcome the specific equity barriers that local farmers are facing.

Legislators we work with are becoming increasingly concerned about extractive rural practices by corporate agribusiness. There is an increased interest from policy makers to pursue regulatory reforms, whether that’s reining in industrial livestock operations or curtailing biogas production due to the fact that it entrenches our dependence on fossil fuel infrastructure and promotes the growth of factory animal production as a means to produce energy.

There doesn’t have to be a trade-off between working on policy in the states and working at the federal level. Rural people need policymakers working at all levels on their behalf.

What is the strategy of your members working in majority conservative state legislatures that often oppose such regulation?

These policies play really well in rural areas, regardless of political ideology. For example, breaking up corporate monopolies is extremely popular among farmers regardless of what political affiliation they subscribe to. One of our members in Iowa has been getting a lot of traction working on this issue in a very conservative district. You have conservative people and then you have the agribusiness lobby, and they don’t always see eye to eye, even though the agribusiness lobby likes to claim that they represent most people and most farmers.

What happens is that in rural areas people tend not to believe that elected officials have their best interest at heart. In my opinion, this is because they have not had the experience of seeing a government working for them.

Regenerative agriculture policy is another example. Maybe many farmers living in rural areas might not believe in “global warming” in the way they have come to understand that term. But rural people and farmers are often some of the first to tell you that they have seen the impact of extreme weather shifts over their lifetimes and are now having to manage their land differently due to the threat of floods, droughts and wildfire.

Whether you’re Democrat or Republican, or anything in between, these climate catastrophes are hitting us all. While legislators may not use terms that have been hyper politicized, they do speak about climate change in the context of the extreme weather events and helping farmers and rural people remain resilient while navigating climate catastrophes.

How would you describe SiX’s mission?

SiX works with state legislators once they are elected to help them govern differently and improve the lives of working people.

Governing is more than just getting elected. Once someone is elected to office, they become responsible for being a decision-maker on a number of issues. Yet with a tsunami of lobbyists coming at you, how do you center the lives of people most impacted by your policy decisions? In many states, state legislators are simultaneously underpaid and woefully understaffed but expected to become experts on a whole host of issues that they may or may not have any direct experience with. In many states, they are doing all of this while working a second job to pay the bills. Understanding the reality of what legislators face, SiX steps in to help build capacity for state legislators working on progressive policy to do their jobs better and more impactfully.

Not everybody who runs for office is an organizer. What SiX does is help people learn how to strategize and how to organize in partnership with communities who are the most impacted.

We provide state legislators with resources and knowledge on a variety of policy issues, and connect them with community partners who don’t have a regular presence in the statehouse. We also work to help the legislators connect with colleagues in other states so they can learn about the key issues and players and discuss strategy. Lastly, we organize together with legislators and partners to build a shared state policy strategy.

In Minnesota, a state with a Democratic trifecta since January 2021, the legislature has been very successful in passing progressive legislation. How do you explain that?

Minnesota was primed and ready to move when they had the opportunity. The exciting policies that have recently passed in Minnesota are testament to the power of all of the community-based organizing that has been happening for years, combined with state elected officials who were prepared and ready to move an ambitious agenda forward. It cannot be understated how important continual power building is, so that when the opportunity to make change comes, the legislative body can act swiftly to move an agenda that serves the people.

Oregon is another example where we saw this happen during the last legislative session, but around a particular issue. Factory farms have been a big problem in Oregon for the last couple of decades. Notably, factory farms have been expanding into areas where people feel they don’t have political power. In 2023, after 20 years of organizing in the state, there was finally political will to implement greater state regulation around factory farms with the passage of Senate Bill 85, a new law that established stricter regulations for the operations at the state level and returned some local control to counties over the siting of facilities. State legislators, together with advocates and impacted communities, drove the regulatory reforms forward.

We are excited to see deep partnerships coming together and amazing things happening in both states that are traditionally more conservative and states that are traditionally more progressive. I see rural work as really being a place where we can cross political ideologies and do what’s right by working people.

Joel Bleifuss is Barn Raiser Editor & Publisher and Board President of Barn Raising Media Inc. He is a descendent of German and Scottish farmers who immigrated to the Upper Midwest in the 19th Century to become farmers in Wisconsin, Minnesota and the Dakotas. His grandmother was born in the Scottish Highlands to parents listed in the Census of Great Britain, 1881 as “farm servants” on land owned by the Duke of Fife. Joel himself was born and raised in Fulton, Mo., a small town on the edge of the Ozark Highlands. He got his start in journalism in 1983 as a feature writer and Saturday reporter/photographer for his hometown daily, the Fulton Sun. Bleifuss joined the staff of In These Times magazine in October 1986, stepping down as Editor & Publisher in April 2022, to join his fellow barn raisers in getting Barn Raiser off the ground.

Justin Perkins is Barn Raiser Deputy Editor & Publisher and Board Clerk of Barn Raising Media Inc. He is currently finishing his Master of Divinity at the University of Chicago Divinity School. The son of a hog farmer, he grew up in Papillion, Neb., and got his start as a writer with his hometown newspaper the Papillion Times, The Daily Nebraskan, Rural America In These Times and In These Times. He has previous editorial experience at Prairie Schooner and Image.

Have thoughts or reactions to this or any other piece that you’d like to share? Send us a note with the Letter to the Editor form.

Want to republish this story? Check out our guide.

More from Barn Raiser

Farmers Weigh Harris and Trump on Ag Policy as Candidates Vie for Rural Votes