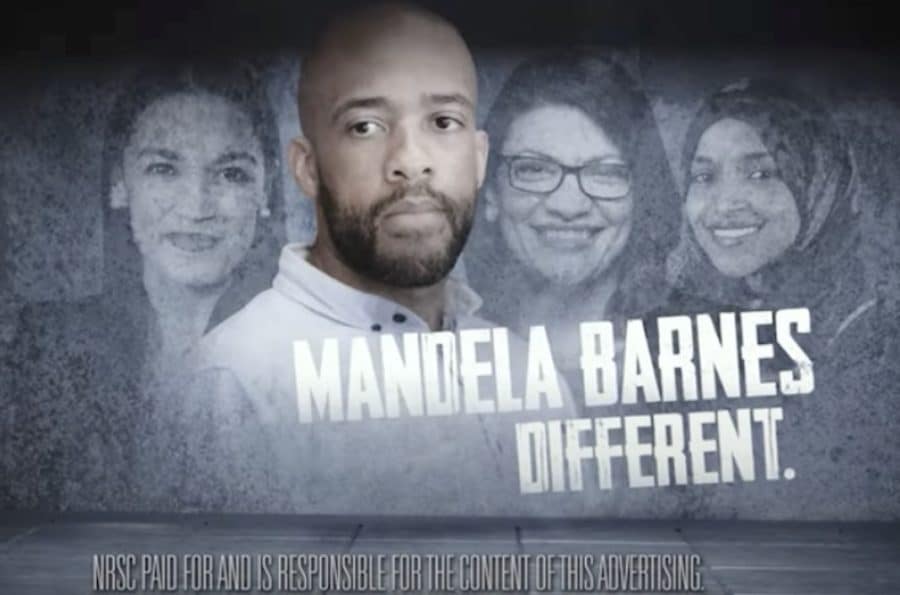

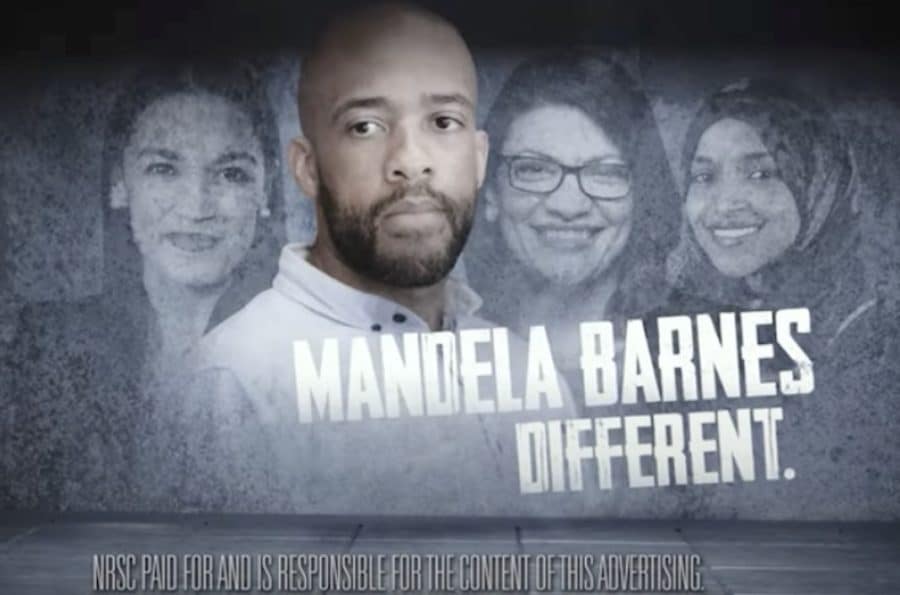

The armchair quarterbacks are out in full force after Wisconsin’s unusual split midterm decision. After an onslaught of strategically racist dark money ads, the Democrat’s first African American top-of-the-ticket candidate, Mandela Barnes, fell just short of unseating incumbent Ron Johnson—49.5% to 50.5%—in Wisconsin’s closest U.S. Senate race in over 100 years. But on the same ballot, moderate white incumbent Democrat Gov. Tony Evers won reelection 51.2% to 47.8%. Like disappointed Packer fans after a close loss, every activist seems to have a pet theory of what someone else—the Democrat Party, the Barnes Campaign—should have done to win the pivotal Senate seat.

The Lesson from the Wisconsin Midterm Elections: Face to Face Makes a Difference

Deep canvassing works well in rural areas where rootedness in local communities is essential

Some say the wrong candidate was nominated, that Barnes, a black man with many ties to social justice groups, provided fodder for racially tinged dark money propaganda; others that they know what magic television ad the campaign should have run or that the national Democrats should have bankrolled even more television on top of an already massive investment in the race.

This incessant punditry renders democracy as just another sporting event, in which “we the people” are mere spectators shouting from the bleachers at the players. But unlike sports, where fans can never hit a homerun or score a touchdown, a healthy democracy depends on ordinary people playing the leading role.

Thinking Like Organizers, Not Pundits

We should look at elections like organizers not pundits, shifting orientation from that of spectators to participants. The election results look different when we center the latent power of like-minded people to reclaim our democracy when they band together in common purpose. Effective organizing focuses on both the external situation and the agency of average people, finding leverage points where engaged citizens can make the marginal difference in outcomes. Without effective strategy and tactics, informed by what organizer’s call power analysis–honest and on-going assessment of the relative capacity of opponents, allies, and other actors to influence outcomes–grassroots organizing efforts will fail and thereby demobilize its own base of support.

From this perspective, the near miss in Wisconsin’s midterms is promising. In 2022, the trend toward closer and closer elections continued. As I will detail below, according to the data, deep two-way conversations with voters are a strikingly effective tool. If more funders put more money into election-focused community organizing that uses evidence-based engagement tactics, and more concerned citizens get off the sidelines, we have the potential to turn the tide, and overcome the kind of corrosive propaganda campaign that defeated Mandela Barnes.

First, Wisconsin’s new normal of historically close margins gives engaged citizens the potential power to change outcomes when they act together at the necessary scale. The state’s presidential elections were within 1% in 2000, 2004, 2016 and 2020. Now midterm elections are becoming just as close, as national issues have displaced more provincial concerns during the pitched battle between Democrats and the MAGA wing of the GOP over the fate of democracy. The last two midterms (2018 and 2022) produced the state’s two closest gubernatorial contests since 1964, and this year was the first in Wisconsin history with close gubernatorial and U.S. Senate elections on the same ballot. Barnes lost by only 26,000 votes (out of 2.9 million votes cast), a margin grassroots organizing has the potential to shift.

Second, although Wisconsin as a whole has been roughly 50/50 in most presidential elections for two decades, on a county-by-county level the vote composition is changing rapidly. This means there are many voters in motion who have yet to form habitual voting patterns. It is axiomatic among political scientists and political professionals that the voters most likely to shift partisan allegiances from election to election are those who have recently shifted or split their ballots between the parties. This means this group is in general the most persuadable.

The challenge for organizing is that these voters are not concentrated in one geography. Wisconsin is experiencing a density divide where voters in Wisconsin’s urban areas and older suburbs are trending more Democratic each cycle, and those in rural areas, towns and exurbs are increasingly moving to the GOP. Democrats gained 87,000 net votes in the 15 largest counties but Ron Johnson benefitted from double digit increases in vote share in 20 predominantly rural counties.

Some of this change is demographic and a result of migration patterns, but the rapidity of the shift indicates that the larger influence is shifts in individual voting behavior. This means organizers cannot put all of our eggs in urban, rural or suburban organizing, especially in Wisconsin where the population is distributed across all three sectors.

The benefits could be especially large in Wisconsin’s rural areas, which account for roughly 30% of the state’s population, where Democrats have disinvested and there is comparatively little community organizing. Research on successful candidates shows that local roots and knowledge, and the ability to listen and form relationships, are critical to increasing Democratic vote share in rural areas, strongly suggesting that deeper community organizing could help slow the rightward drift.

Third, although swing voters matter because elections are so close, they are not the only important target. Wisconsin has evolved into a state where base turnout is the dominant vote driver. Over the last two decades the proportion of Wisconsin ticket-splitters had declined by 75%. Only 5% of voters switched parties in selecting their preferred gubernatorial and Senate candidates this year. With 95% of Wisconsin voters not splitting their tickets in 2022, it was the ability of Democrats to match high GOP turnout that put moderates in a position to benefit from the marginal impact of a much smaller group of swing voters.

Because Wisconsin elections are so close the small fraction of swing voters can make the difference in victory or defeat, but only when each party fully mobilizes their much larger number of base voters. This throws a wrench into the narrative of those Democratic consultants and politicians who are bent on reducing the rising influence of progressives like Vermont’s Bernie Sanders, and like-minded elected leaders in Wisconsin, in the party.

These campaign professionals, joined by many Monday morning quarterbacks, are dangerously misinterpreting the outcome of the 2022 midterms. They have concluded that moderate candidates like Evers will outperform progressive candidates like Barnes who are more vulnerable to right-wing smears on crime, immigration, CRT, and other GOP cultural wedges.

Given high GOP turnout, however, moderates can’t win unless voters with progressive views turn out in high numbers. Since 2000 the progressive share of Democratic voters nationally has increased from 28% to 51%. In the dozens of public and non-public poll crosstabs I reviewed this year, the proportion of Wisconsin Democratic voters who describe themselves as somewhat or very progressive ranged from 55% to 58%.

Evers might well have lost without a young charismatic candidate like Barnes at the top of the ticket, mobilizing voters who crave a positive progressive agenda on racial justice, climate, health care and economic security. Further, as I will discuss below, it is a fallacy to confuse swing voters with moderate ideological views.

The organizer’s takeaway is that to influence election outcomes we need to talk both to base voters to drive higher turnout—especially among lower participating groups such as young people of color—and to likely voters who are persuadable if we have deeper conversations with them that address their concerns and the fears raised by right-wing cultural wedges.

Fourth, more spending on expensive television ads is not the best path to victory. Instead, the Wisconsin Senate race provides encouraging evidence that ramping up investments in deep canvassing, and more activists willing to get off the sidelines and make phone calls and knock doors, is more effective in countering the scurrilous billionaire-funded propaganda than responding in kind.

In the Wisconsin Senate race, Democrats went all out to match GOP spending, but were badly outgunned. In the post Citizens United legal framework, both official campaign spending and rapidly accelerating dark money spending on behalf of candidates by independent groups must be considered. According to preliminary data, the Barnes campaign actually outspent Johnson by $4 million, but with independent money the Democrats could not keep up. Although the Democrats and their allies spent an astounding $72 million on the senate race, the GOP with its greater access to billionaires spent a combined $104 million. Republicans used this funding advantage to outgun the Barnes campaign with an onslaught of fear mongering and racially coded crime ads that make the infamous Willie Horton campaign look tame. If Democrats had moved even more resources in the final weeks to narrow the gap they risked losing other tight races in Nevada, Georgia, Arizona and Pennsylvania.

This is an arms race Democrats cannot win. Yet as Kara Voght reports in Rolling Stone, the Monday morning quarterbacking among Democrats is focused on advertising tactics. It is far from clear that more ads would have blunted the impact on the relatively small subset of swing voters that put Johnson over the top, given that Democrats have yet to develop an effective rebuttal to the crime panic fomented by the GOP, which is grounded more in racialized fear than public policy.

The Answer is Not More Propaganda, But Actually Talking to Voters

A growing body of evidence indicates that many voters are not purely for one side or the other, nor are they moderate. Instead, they are cross-pressured. Many who may be triggered by racialized ads fomenting fear about crime and immigration also support progressive policies. This is why recent research on rural shows, contrary to the conventional wisdom of many Democratic consultants, progressive populist messages are highly effective.

As a result, a deeper conversation where a volunteer from the same region listens, talks through misleading claims they have seen on television if they are raised, and walks through the candidate positions on the issues the voter identifies as most important to them and their communities, is more impactful than traditional campaign tactics. One study found it 102 times more effective than TV and other traditional campaign tactics.

Starting in 2020, the organization I lead, Citizen Action of Wisconsin, and other affiliates of the national organizing network People’s Action, started using a deep canvass methodology, drawn from traditional community organizing, where volunteers and local organizers have tens of thousands of in-depth conversations with voters. In Wisconsin in 2022 we made a combined 109,000 phone calls and door knocks in rural, suburban, and urban areas.

The results are extremely encouraging. During these conversations nearly 11% of voters moved from undecided or leaning towards Ron Johnson to supporting Mandela Barnes.

This commonsense approach works especially well in rural areas where rootedness in local communities is essential. Deep canvassing, and a candidate who campaigns by talking to folks, helped State Sen. Jeff Smith win reelection against a well-funded challenger in a rural Western Wisconsin district. As organizer George Goehl documents, in 2022 deep canvases by People’s Action affiliates in the rural regions of North Carolina and Michigan played an essential role in moving rural voters to support progressive candidates.

The deep canvassing technique of organizing one conversation at a time supports Philosopher John Dewey’s view that “the cure for the ills of democracy is more democracy.” That does not mean repeating the mistakes of the past. Dewey also warned that democracy cannot be saved by “introducing more machinery of the same kind as that which already exists.”

Getting to the scale of deep conversations needed to counteract the toxin of propaganda afflicting our elections requires a change in investment strategy. We need to invest in the organizing infrastructure and training which empowers citizens to, collectively, have millions of real conversations with other voters who live in their communities. This person-to-person connection at a large enough scale will impact campaign outcomes, but only if more citizens stop acting like Monday morning quarterbacks, get off the sidelines, and play an active and constructive role in reclaiming American democracy.

Robert Kraig is the Executive Director, Citizen Action of Wisconsin. Robert has two decades of experience in social justice and labor organizing. He took the helm in September 2009 at the height of the Great Recession when social justice groups like Citizen Action of Wisconsin were in financial danger, and has led a dynamic team of organizers in rebuilding it into one of the leading progressive forces in Wisconsin. Robert is the former Wisconsin State Council Director for SEIU, where he helped develop and win the passage of several policy innovations which enabled over twelve thousand low-wage workers to form unions. Robert's focus is on the nexus between communications and progressive strategy. He has an academic background in political persuasion, earning a PhD in Rhetoric at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1999. He has published one book and multiple peer reviewed academic articles on the history of American political rhetoric.

Have thoughts or reactions to this or any other piece that you’d like to share? Send us a note with the Letter to the Editor form.

Want to republish this story? Check out our guide.

More from Barn Raiser

How Safe Is Fluoridated Water? A Look at New Research